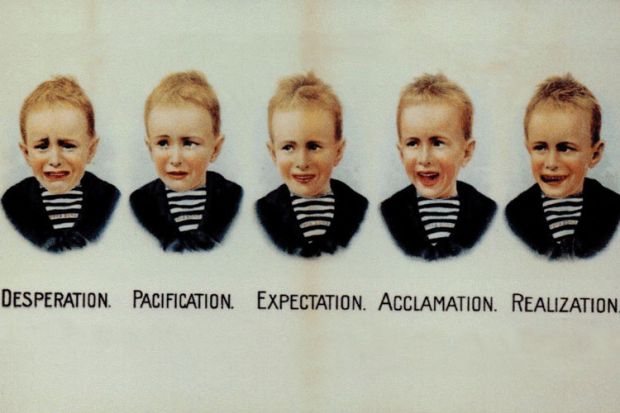

There is a fashionable notion that ultimately neuroscience and biology will have definitive answers as to what emotions are, and how they function. Tiffany Watt Smith, in this entertaining exposition of 156 polyglot emotion terms, demonstrates how emotions straddle biology and culture, subjective sensation and social communication, so that history, anthropology, politics and linguistics are indispensable to understanding them.

In physiological terms, says Watt Smith, a blink and a wink are virtually identical. “But you need to understand the cultural context to appreciate what a wink is. You need to understand playing and jokes, and teasing and sex, and learnt conventions like irony and camp.”

Although they are often instantaneous and involuntary, emotions, unlike the neuron-firings, reflexes and sensations they involve, are about people and things; they are imbued with meaning. They are therefore dependent on the emoter’s whole history, indeed on the history of her culture and language.

“What’s in a name?” you may protest. Could there really have been no unconscious or repressed feelings before Freud? Surely the German term Schadenfreude seems a neat fit for a feeling well recognised by, say, the English. And liget, the term vaunted by anthropologists as typifying the concept-dependence of emotion, can surely apply as much to testosterone-driven delinquents in London as in the remote Philippines. Perhaps, but what is being the same as what?

Watt Smith may be too extreme in suggesting that perhaps no one felt emotions of any sort before 1830 (when the word “emotion” became current), but experienced instead “accidents of the soul” or “moral sentiments”. Yet can a feeling, differently delineated, explained and contextualised in different eras and belief systems, properly be considered to be the same phenomenon in each, and just differently labelled?

What were once spiritual visitations have become unwanted pathologies, which in turn have become unmedicalised and often desirable states of mind; and the opposite. Does acedia, a depleting malaise inflicted by “noonday demons” on medieval monastics, map on to Renaissance melancholy attributed to an imbalance of the humours? Does either of these really equate with depression, now seen as a neurochemical condition, and, as Watt Smith says, diagnosed excessively in blatant disregard of the distinction between warranted and unwarranted sadness?

During the American Civil War, “homesickness” was a life-threatening illness that earned soldiers honourable discharge from the army. Doctors in ancient Rome and medieval Europe advertised cures for “love-sickness”. Now we (mostly) love being in love; although, as La Rochefoucauld observed, “some people would never fall in love if they hadn’t heard love talked about”.

Moral, as well as scientific, evaluation will “determine whether we greet a feeling with delight or trepidation, whether we savour it or feel ashamed”, says Watt Smith. Guilt was a reprehensible fact in a religious world, but has evolved into a superfluous sensation. Envy, even now that it is no longer one of the seven deadly sins, remains shameful in most European cultures, so perhaps our furtive, uncomfortable feeling is not at all the same thing as the Ifaluk word transliterated as “song” – a perfectly justified, indeed praiseworthy, indignation at anyone who infringes the key Ifaluk value of equitable sharing.

Surely feelings about feelings change the feeling that those meta-feelings are about, and hence the composite, overall emotion that results. Watt Smith charts the shifting fads, fantasies, science, metaphysics and metaphors that make emotions what they are. Witty, informative, undogmatic and thought-provoking, this wonderful book should convince us that emotions are never just neural events.

Jane O’Grady is visiting lecturer in philosophy of psychology, City University London, and co-founder, London School of Philosophy.

The Book of Human Emotions: An Encyclopaedia of Feeling from Anger to Wanderlust

By Tiffany Watt Smith

Profile Books/Wellcome Collection, 208pp, £14.99 and £9.99

ISBN 9781781251294 and 9781847659675 (e-book)

Published 17 September 2015

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login