Andreas Weigend, former chief scientist for Amazon, intends Data for the People to be a positive, uplifting book, presenting a wonderful future in which the great benefits of big data are empowering and liberating. Weigend is careful to reassure us that his “post-privacy” world is nothing like George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four – the opening sequence is about his childhood experience of the Stasi – but he doesn’t seem to notice the echoes of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World.

Privacy is dismissed in a few short paragraphs. Weigend’s “brief history of the brief history of privacy” is disappointingly predictable – falling into the familiar trap of suggesting that in the past our lives were lived “in public”. It is a seductive myth that misses historical and cultural evidence, from religious practices to folklore from all over the world. It is a convenient myth, however, for those who benefit from our abandoning privacy.

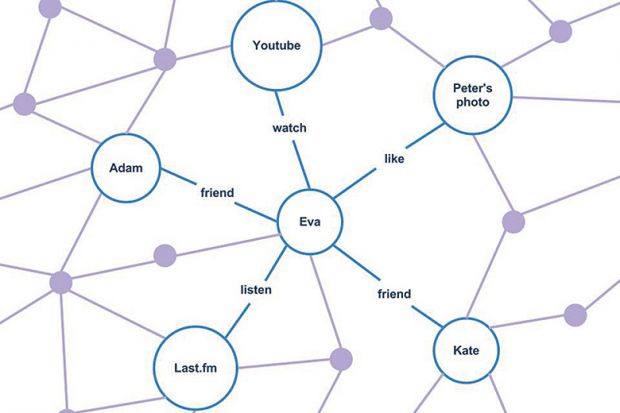

Having summarily dismissed privacy, Weigend describes the Brave New “post-privacy” World. The analysis of Facebook’s “social graph” is excellent, as is the description of the “sensorization” of society – where so many things monitor and record so much about us – but Weigend’s critical analysis is limited: he sees part of the problem but misses more. He lauds Facebook’s notorious “emotional contagion” experiment while glossing over the ethical issues and embraces Google Glass while failing to even mention the privacy-related failure of that project.

Weigend’s “solution” is a series of rights over “data refineries” (extending the dubious “data is the new oil” analogy). These are interesting, but the naivety about their effectiveness is palpable. He suggests data refineries should give us access to the “knobs” that control their algorithms, so we can experiment. An admirable idea – if you have enough time, expertise and understanding. For most it would be meaningless; few would even try.

This is the book’s fundamental weakness. It accepts what should be unacceptable as unchangeable, while proposing changes that would do almost nothing for most but exacerbate power imbalances, widen digital divides and drive us into a Brave New World that works for Alpha-Pluses, less well for Gammas and Deltas, and not at all for those who don’t “fit”. When Weigend writes blithely about the rewards of abandoning privacy outweighing the risks, it is hard not to connect this with his being a white, rich, highly educated and tech-savvy male in a (for now) liberal democracy – and neither a dissident nor a whistleblower.

Huxley has a leader in his Brave New World rail against people having once wanted “the liberty to be inefficient and miserable”. Weigend seems to have similarly disturbing feelings about inefficiency. He has a particular dislike of randomness, and wishes to remove it wherever possible – when for many serendipity is one of life’s greatest pleasures. The section on health is fascinating – the possible benefits of extensive data sharing are enormous – but ultimately particularly chilling. Data will determine our access to healthcare and lifestyle choices. Weigend is direct: “occasionally what the data orders will be tough medicine”. So read this book – with a critical eye – but then (re)read Brave New World to remind yourself what needs to be fought against.

Paul Bernal is lecturer in IT, IP and media law, University of East Anglia Law School, and author of Internet Privacy Rights: Rights to Protect Autonomy (2014).

Data for the People: How to Make Our Post-Privacy Economy Work for You

By Andreas Weigend

Basic Books, 272pp, £18.99

ISBN 9780465044696

Published 16 February 2016

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login