Warships that encircle the planet, guns that kill at half a mile or more, written constitutions that allocate your rights and duties: all these are crucial features of modernity and, according to Linda Colley, they are functionally connected. The guns and ships create global possibilities for war and empire. The written constitutions are necessary because men (literally) have to be taxed and enlisted and – more generally – incorporated into the polity.

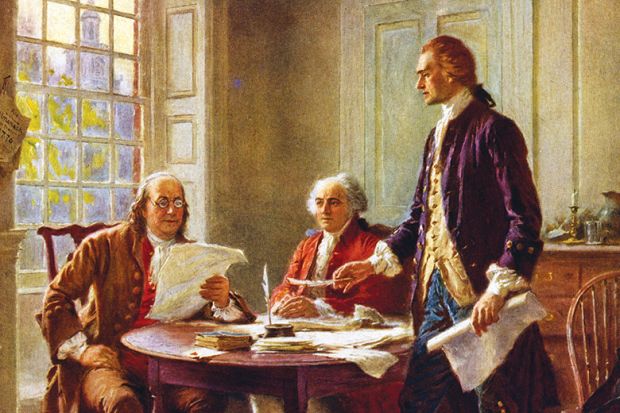

The proliferation of written constitutions after 1750, aided by increases in literacy and the falling costs of printing, is undeniable. Political theorists such as Rousseau and Bentham could normally be assumed to be working on a constitution for somewhere, a case of general principles tweaked for particular circumstances. Colley insists that even the most unlikely autocracies were keen to be seen as being on the constitutional route. Catherine the Great’s Nakaz, her thoughts on politics and legal arrangements, were sufficiently radical to be banned by the French censors. A century later, in 1889, after the collapse of the Shogunate, the emperor posthumously known as Meiji approved a constitution for Japan. Even in Britain, there was a great deal of scholarly argument about the “unwritten constitution” we were assumed to possess already and a kind of exhumation of Magna Carta. In this context, the US constitution of 1787 was anything but exceptional.

Hats off to Colley for giving us a book on the modern world that ranges widely and reads well. Sometimes the range seems rather random. For instance, we read of a Corsican constitution in the 1750s (Pasquale Paoli’s, not Rousseau’s) and then we travel across the world with the Seven Years’ War (1756-63) and Corsica seems forgotten, but a French defeat in 1794 precipitates the British occupation of Corsica, rendering constitutional devices irrelevant.

The author is unafraid of counter-factuals: if France had succeeded in forming a proper alliance with Spain during the Seven Years’ War, then she would have maintained a military presence in North America and the anglophone population would have needed British protection – so no USA. Some historians disapprove of narratives as broad and speculative as this one. (She can’t possibly understand all those languages.) But surely we need this kind of history as well as the rigorous, detailed stuff.

The making of constitutions has continued and even accelerated in the postcolonial era. On the whole, I am inclined to see the process from a more sceptical angle than the author. The constitutions and the doctrines that underlie them are a product of the hegemony of the Enlightenment, brought about by the erosion of traditional and religious beliefs. That does not mean that people believe the new doctrines. Rather, they are what Bertrand Russell called “Sunday truths”: we claim to believe them but act as if we don’t. I am reminded of the tale told by a friend who grew up in the USSR. He was involved in the “widespread consultations” on the 1977 “Brezhnev Constitution”, an even more liberal document than the “Stalin Constitution” of 1936. The consultative meetings, he said, were typified by “massive amounts of booze, massive amounts of cynicism”.

Lincoln Allison is emeritus reader in politics at the University of Warwick.

The Gun, the Ship and the Pen: Warfare, Constitutions and the Making of the Modern World

By Linda Colley

Profile Books, 512pp, £25.00

ISBN 9781846684975

Published 11 March 2021

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login