Forty-three years ago, the South Australian Institute of Technology, an antecedent institute of the University of South Australia, was the trailblazing institution in Australia for the provision of opportunity and education to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students. The Aboriginal task force was formed at SAIT and, after that, everything began to change for the better across the country, with targets and commitments for Indigenous student participation and pathways that originated in South Australia being emulated and adopted by all higher education institutions in the land. Fast forward 40-odd years, and an Irish-born vice-chancellor was setting out for a remote Aboriginal community to discuss the end of a tailored Aboriginal education programme with the traditional owners of those lands.

The Aṉangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands is a region of approximately 100,000 square kilometres (39,000 square miles) in the far north-west of South Australia. It’s pretty much the same size as South Korea, but has a population of only about 2,500 people, mostly concentrated across a series of remote Aboriginal communities in what is, undeniably, the Outback. The APY Lands were created through a land rights act in 1981 and operate as an Aboriginal local government area, administering the land in accordance with the wishes of the traditional owners. Nearly four years ago, when I was interviewed for my role as vice-chancellor of the University of South Australia, I distinctly remember a panel member asking me what I knew about Aboriginal and Indigenous Australia. At the time (and knowing honesty is the best policy in such circumstances), I answered that I knew nothing more than the art I had seen since my arrival in the country and what little I had read in books or seen in film and cinema. This lack of knowledge apparently didn’t negatively impact on my candidacy and, in the intervening years, I’ve made it my business to learn considerably more. However, as any educator knows, learning by doing is the ultimate method, and so it was I headed off from Adelaide to see for myself what Aboriginal Australia and, in that context, remote education, was really about. We were also venturing into a community openly grieving the tragic loss of nurse Gayle Woodford, (who had recently and tragically been murdered) and emotions were high. Coming as I do from quite literally the far side of the planet, I wasn't quite sure what to expect.

The trip from Adelaide to Alice Springs was straightforward: Alice is a well-served destination and the flight was comfortable in a still-warm autumn sky. On arriving to collect our hire car, I began to get a feel for what lay ahead. For one thing, the car wasn’t simply a car. It was a white 4x4 Toyota Land Cruiser "ute" – quintessentially Australian, in a Japanese way. As my licence was copied in the office, I took in the posters adorning the walls: images of cars upside down on desert roads; an interesting image of a unique and unfortunate car-camel union; advice about the use of satellite phones and the importance of planning and registering routes. Not your average car-hire type advice.

We loaded up the truck and tied down the tarpaulin, and then headed out of town. I was driving, I like driving – and driving across the Australian outback is really driving. The Toyota was a diesel manual and its clunky gearbox and throaty, high-revving engine portended its suitability for the terrain we were about to enter. The first 100 kilometres was on a tarmacadam highway, easy going, until the single largest road train I have ever encountered barrelled past with its monstrous cab, four semi-trailers and who knows how many wheels thundering, creating a slipstream in its wake that threw our not-insubstantial vehicle about the place – a timely reminder that we were not in Kansas any more. The next 350 kilometres was more interesting (and more fun) – unsealed roads, corrugations, ruts, sinkholes, sand and dust, and on which our lead vehicle (which I was following) was cutting a swathe at a heady 110 kilometres per hour. I figured that this was a test – let’s see if the v-c can actually drive – and so kept pace with their dust cloud. It was a little like driving in fog, but fog that you can taste through the air vents, and that coated everything in hues of pale ochre and red. The landscape was truly spectacular – a quasi-Martian landscape of red earth, desert and scrub, spinifex and fingerbone-like trees and then, unexpectedly, meadows of buffel grass and spectacular blooms of desert flowers. It had rained copiously some weeks prior and the desert had blossomed, and the lakes and creeks had filled (as had some interesting mudholes on the road), all thanks to the big wet. Cows and camels were abundant and grunted their disapproval as our mini-convoy sped past.

We arrived at our destination after three-and-a-half hours off-road. I was rather pleased with myself: the car and its occupants were all in one piece. The closest we had come to disaster was encountering a large-ish cow that materialised in the middle of the road in the middle of a dust cloud. My cat-like reflexes had ensured that said cow now had a very exciting dinner-party story to impart to its peers of the time it had stared down the white Toyota of doom, which, defeated, slunk past at 110 kilometres per hour in a semi-sideways fashion.

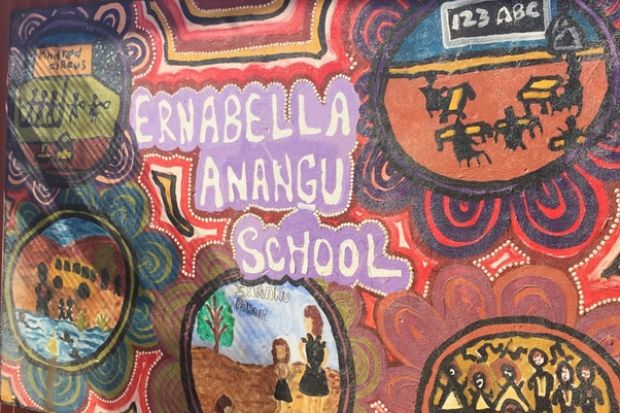

In 1984, our antecedent institution, the College of Advanced Education, began delivery of the Aṉangu Tertiary Education Programme (Aṉtep) in Ernabella, a township of about 350 people, 1,400 kilometres north-west of our main campus in Adelaide. The programme was established to provide formal teaching qualifications for Aṉangu, the local Aboriginal community, enabling them to educate others in their communities. Pitjantjatjara is the first language of this community; English is a distant, seldom-used second. The programme provided a basis for bilingual education, pairing Aṉangu teachers and teaching assistants alongside non-Aboriginal teachers in the classroom. The programme has enjoyed many successes across a long and proud tradition, but accreditation externalities have precipitated a need for change; indeed, they were dictating the end of the programme in its current format, and our visit was to discuss this with the community and to begin to plan for the future. Visiting the local school, where anything above 50 per cent attendance is a good day and which has seen painfully few Year 12 completions in recent years, I began to fathom the importance of the programme. This was not downtown metropolitan Adelaide. The normalities of suburban life were absent and the expectations around schooling and achievement were very different. The children at the school need tailored support, and cultural competence here is every bit as important as curriculum. The teachers were, uniformly, magnificent in their dedication.

On rounding a corner at the APY administration centre in Umuwa we happened upon a man called Gordon Ingkatji and his daughter Nyunmiti Burton. Gordon is a fellow of our university and Nyunmiti is an alumna. Gordon doesn’t know exactly how old he is. He was born in approximately 1931 and his early years were lived pre-contact – without encountering any white people at all. He attended Ernabella mission school when it opened in 1940. An injury meant that he couldn’t work on the land and so he was taught to type. Lucky for us: he went on to document his own language, which led to a Pitjantjatjara vernacular language programme in the school and ultimately the creation of the Aṉtep programme in our institution. We talked about how important the programme was to the community. We talked about bringing more content from the university into the community.

On reflection, what I didn't really understand was how impactful the University of South Australia has been in the lands. The number of alumni we encountered was, quite frankly, astonishing. Across the days, we would find graduates, Aṉangu and non- Aṉangu, in the community who told us their stories of how the university and Aṉtep had shaped them, empowered them or inspired them. We also met current students, from our pathway programme in UniSA College, whose passion for learning and belief in the transformational power of education for their community was palpable and inspiring. A barbecue we had on our second night could just have well been badged as an alumni event. As the snags sizzled and the heavens turned on a magnificent display overhead and Waltzing Matilda was sung in Pitjantjatjara, I was thinking to myself: you can read reports, listen to updates, infer some level of understanding from what you hear around the traps, but you never really grasp the essence of a thing until you experience it yourself.

The provision of teacher training education can be fraught. Multiple and contrary opinions abound around student quality, curriculum pedagogy, theory and practice. In Australia, accreditation and registration bodies take a view, and assert influence at state and federal levels. Ministerial and parental advocacy and anecdote can often be placed at odds with institutional autonomy. It’s little surprise then, that a 30-year-old niche teacher education programme that was designed to do a very specific thing for a very specific group of people has fallen foul of disconnected, external regulatory forces. That doesn’t necessarily make those regulating, right. One size clearly does not fit all. Circumstances differ. Communities and cultures differ and must be respected. As Australia grapples with the politics of securing a sustainable funding base for higher education, it shouldn’t lose sight of the impact higher education has in remote communities. Expanding the demand-driven system to include sub-bachelor and enabling and foundation pathway programmes can only deepen that impact.

I like to think of our university as a “for benefit” organisation. At the end of the day, it means that we, as the provider, have both a duty of care and a duty to work harder, in partnership with community, to make things better. Our students, their community and future generations of students deserve no less. Driving out of the lands was just as exhilarating as driving in, because driving out, I knew that I would definitely be coming back again.

David Lloyd is vice-chancellor and president of the University of South Australia.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login