English universities that have shifted their recruitment towards international students are not “lining their pockets” but rather are barely managing to maintain their unit of resource, research shows.

Analysis by consultancy dataHE estimates that 54,000 UK 18-year-old applicants were left without a university place at the end of this summer’s admissions cycle after rejection rates reached a new record among the most highly selective institutions. The school-leavers who did get in were more likely to have had to settle for a place in a lower-tariff university.

While this comes after high-tariff universities significantly expanded their intakes over the Covid-19 pandemic, when the use of estimated marks rather than exam scores led to significant grade inflation, these prestigious institutions have been criticised for shifting their recruitment pronouncedly towards international students, who pay tuition fees that have risen rapidly to average £23,750 a year at the most selective campuses.

These universities have faced accusations of feathering their nests while leaving British school-leavers without a university place. Among this group of institutions, higher fee payers now account for 23.5 per cent of students, having remained at about 14 per cent until 2017.

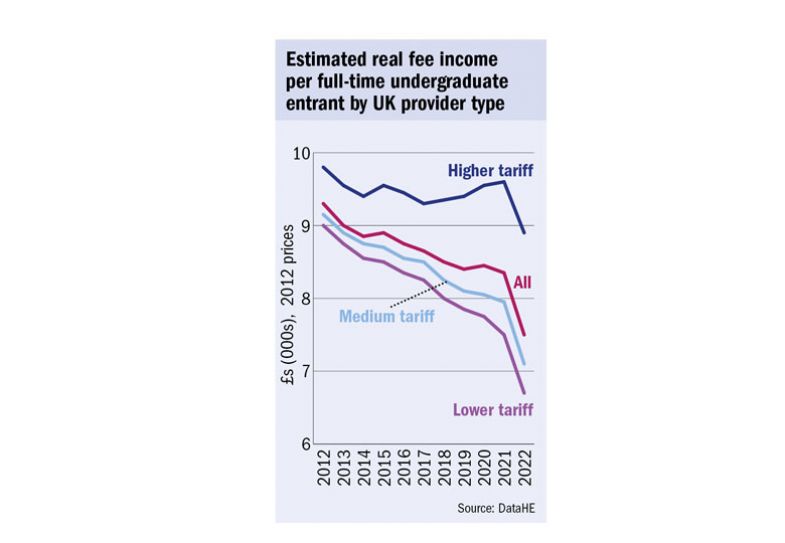

But the analysis by dataHE co-founder Mark Corver shows that rising inflation means that domestic fees – which have increased only slightly over the past decade, to £9,250 – are now worth just £6,500 in 2012 prices, which is most likely less than the cost of providing a place.

Meanwhile, international fees are worth £16,650 in 2012 prices, only about £2,000 higher than a decade ago.

This means that the unit of resource per student – domestic or international – has remained at about £9,500 at higher-tariff institutions over the 10 years, before dropping to £8,900 this year.

“Higher-tariff providers are not ‘lining their pockets’, as some have put it,” Dr Corver said.

For less prestigious institutions, which cannot demand such high fees for international students and which recruit far fewer of them, the situation is far more desperate.

Dr Corver’s analysis suggests that the unit of resource in 2012 prices now stands at £7,100 for medium-tariff providers, and £6,700 for the least-selective institutions.

He said universities might consider reducing their staff-to-student ratios, although this would harm the student experience. And he warned that shifting towards more international recruitment carried growing risks, with institutions increasingly targeting one-year master’s students rather than undergraduates, who guarantee three years of income, and looking at higher-risk source countries.

Dr Corver said UK universities were facing the “worst of all worlds”.

“The combination of high inflation, not having any government backstop and not being able to respond in a normal market way by increasing your prices means you have all of the disadvantages of being in a market but none of the advantages,” he said.

One solution would be to raise tuition fees, but no political party would advocate for this, he predicted, so a “wholesale rethink” of funding was needed.

“Paradoxically, it’s in students’ interests to argue that the fee is too low because it’s beginning to reduce their chances to get in and, for those who do get in, universities have far less money than they did previously,” Dr Corver added.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login