The British-born virologist who shared this year’s Nobel prize for medicine has called on award committees to be more “inclusive and expansive” when recognising scientific achievements but has dismissed speculation that he might have turned down science’s top award because his collaborators had not been recognised.

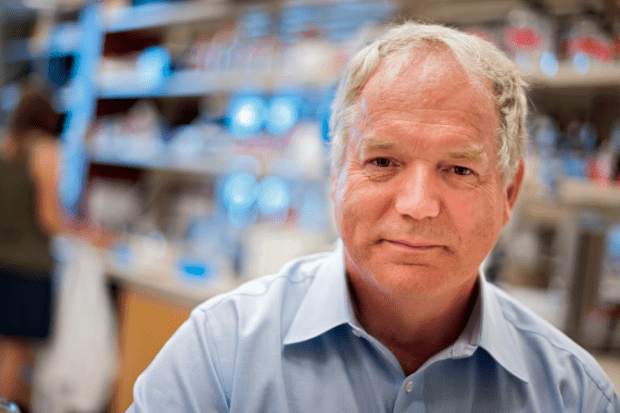

When Michael Houghton was named one of three winners of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on the hepatitis C virus on 5 October, some pundits flagged the London-born scientist’s previous criticism of other academic awards that, like the Nobels, have chosen to honour only a select group of individuals linked to a scientific discovery.

In 2013, Professor Houghton, who is the Canada Excellence research chair in virology and Li Ka Shing professor of virology at the University of Alberta, turned down the C$100,000 (£58,000) Canada Gairdner International Award because his colleagues Qui-Lim Choo and George Kuo, with whom he worked for seven years at the California-based biotech firm Chiron, were not recognised.

However, at a press conference this week, Professor Houghton said in response to a question from Times Higher Education that it would be “too presumptuous of me to turn down a Nobel”.

“The Nobel is the longest traditional prize – in all fields, not just biomedicine – and their regulations and processes are based on Alfred Nobel’s will,” said Professor Houghton.

His decision to reject the Gairdner Prize was an entirely different situation, he explained. That prize, first awarded in 1958, was not as long-standing as the Nobel, and other newer scientific prizes had been more flexible with their rules, Professor Houghton said.

In his case, he had engaged in a discussion with the prize’s committee in the hope that it “could break a few rules”, he explained.

However, discussions had become “a little heated” and he felt unable to accept the prize, despite regretting the “embarrassment” that he, “a visitor”, had caused by snubbing one of Canada’s top biomedicine prizes, he said.

“I was trying to influence how awards are given,” explained Professor Houghton, who said he believed that newer prizes that modelled themselves on the Nobel – with its maximum of three winners per prize – could instead be “more inclusive and expansive”.

Major breakthroughs in modern science were not achieved by “just three people but probably six or seven”, he said, adding that, in future, “a number of committees that are not steeped in the tradition [that] the Nobel [committee is] could be more inclusive and expansive” in recognising these broader scientific teams.

“Great science comes from groups of people, and somehow we need to include that into [award] policies,” Professor Houghton said of future prize-giving.

In the case of the Nobel committee, “it was not feasible to discuss these things with them”, he said, referring to its long-standing three-person maximum and the fact that it notifies winners only minutes before announcing their honour.

Professor Houghton, who shared this year’s medicine prize with the US scientists Harvey Alter and Charles Rice, is only the second Canada-based scientist to claim a medicine Nobel, almost a century after its first winner, insulin co-discoverer Frederick Banting, was honoured in 1923. Professor Houghton took a PhD in biochemistry at King’s College London after undergraduate study at the University of East Anglia. He later moved to Alberta and now splits his time between Canada and California, where his family is based.

David Pendlebury, a senior researcher at Clarivate Analytics, commented that Professor Houghton was a worthy recipient of the Nobel given the “public health dimensions of hepatitis C and the importance of this discovery”, but his stance on awards had jeopardised not just his inclusion on the award, but recognition of the achievement altogether.

“History tells us that the Nobel committee has to make hard choices among possible and competing honorees in order to stay within the Nobel prize ‘rule of three’ limit,” said Dr Pendlebury. “With so many worthy discoveries and discoverers waiting, it is always a safer option to choose an award that does not have a priority or credit controversy built in,” he said.

“The surprise was the decision to award [the Nobel to hepatitis C researchers] based on the fact that more than three researchers were instrumental in this discovery, demonstrating how much more global and collaborative the research ecosystem is today than in Nobel’s day.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login