The University and College Union’s annual congress should have been a happy affair. The union had just organised the biggest strike in the history of UK higher education, forcing employers to shelve plans for radical cuts to pensions that many had previously insisted were inevitable. In the process, it had acquired 15,000 new members – an upturn defying oft-repeated claims that the trade union movement is in terminal decline.

Yet instead of basking in that success, its three-day summit, held in Manchester in early June, ended in acrimony, amid some of the most bitter infighting seen in years. A plea for “unity” from Sally Hunt, the UCU’s general secretary, in what she called the union’s “turnaround year” was entirely overshadowed by three walkouts by Hunt and other senior UCU staff members, triggering the shutdown of debate on each occasion. The action followed repeated attempts by delegates to debate motions critical of Hunt – one of no-confidence and one of censure concerning her handling of the pensions dispute. What some saw as a way of holding leadership to account, UCU staff union Unite saw as an unacceptable breach of rules protecting employees’ dignity at work, and an attempt at an unconstitutional coup against Hunt and her team. After the third walkout, the congress was abandoned.

This drama was the culmination of a topsy-turvy year for the UK’s main academic trade union, which, as well as the pensions win, also contained unexpected lows. And those mixed fortunes are shared by academic trade union movements in other countries. The US is witnessing the growing unionisation of PhD student teachers, but Donald Trump’s union-busting policies threaten to make it even harder for academics to undertake collective bargaining. And in Australia, where the National Tertiary Education Union has just marked its 25th anniversary, wins on pay stand against the inexorable rise of the academic precariat.

The discussions in Manchester – which will be resumed at a recall conference on 18 October – could be seen as heralding the arrival of a new wave of younger trade union activists energised by picket line solidarity and desirous of more input and more accountability from their leaders.

“Academics are starting to feel about UCU what they have felt about their universities,” explains Mike Finn, president of the University of Exeter’s UCU branch, which tabled the no-confidence motion against Hunt. “They feel frozen out of any decision-making by their universities and it’s the same with UCU.” He believes that the decision to allow UCU members to vote on an offer from Universities UK to end the pensions dispute in late March without first taking a ballot of union branches was not just a mistake but demonstrated, in the words of Exeter’s motion, a “democratic deficit in the union…manifested through a continuous pattern of unilateral, undemocratic action”. More than 60 per cent of those voting in the ballot backed the deal proposed by Hunt (pictured below).

The striking academics objected to the universities’ intention to replace the Universities Superannuation Scheme’s defined benefit scheme, determining payouts on the basis of career-average salaries, with a defined contribution scheme that would not guarantee any particular level of payout. In this context, Hunt’s consideration of an earlier offer, which would have preserved defined benefit pensions for USS members up to a salary of £42,000 a year, was also wrong, Finn says.

“We feel the dispute lost a lot of momentum by even considering that offer,” he says. “There was a sense that the union’s HQ was completely out of touch with membership.”

At the end of the curtailed congress, almost 150 delegates signed a statement under the banner of “OurUCU” stating that “union members have the right to hold our most senior elected officials to account”. It further urged members to initiate discussions in their branches about democracy in the union. Elsewhere, other new cliques of UCU activists have formed, using Twitter to challenge the union’s direction. These include UCU Rank & File, which characterises its members as supporting “a stronger line from their national union”, and the Branch Solidarity Network, which is “dedicated to organising grass roots campaigning”.

“They are trying to open up a conversation about achieving a lay-led union – it’s not about strategy or factionalism,” says Finn, claiming that Hunt’s approach at the congress was the catalyst for the OurUCU movement. “It sprung up spontaneously, literally in the last few minutes of congress,” he explains. Of the no-confidence motion, he adds: “If it had been debated early on, it would been annihilated at a vote, but what happened in congress changed people’s minds.”

Katy Fox-Hodess, who lectures on work, employment and labour organisation at the University of Sheffield’s Management School, was an early organiser of the UCU Rank and File in the weeks after about 1,000 union activists descended on UCU’s Camden headquarters on 13 March in protest against the proposed pension deal. “We had been on the picket lines in the snow for almost a month – the membership had never been so engaged and there was a wish to keep the fight going,” she explains.

Rank and File’s network is “largely, but not completely, younger members who have not been involved in the UCU Left or Independent Broad Left fights of the past”, she adds. “This is a very different project to UCU Left, which is essentially a political party within UCU – we are a network of activists who share a commitment to building a democratic, militant, politically engaged union,” she adds. “We recognise that if we want to make big gains we have to fight for them – employers are not going to give us what we deserve simply because we ask nicely.”

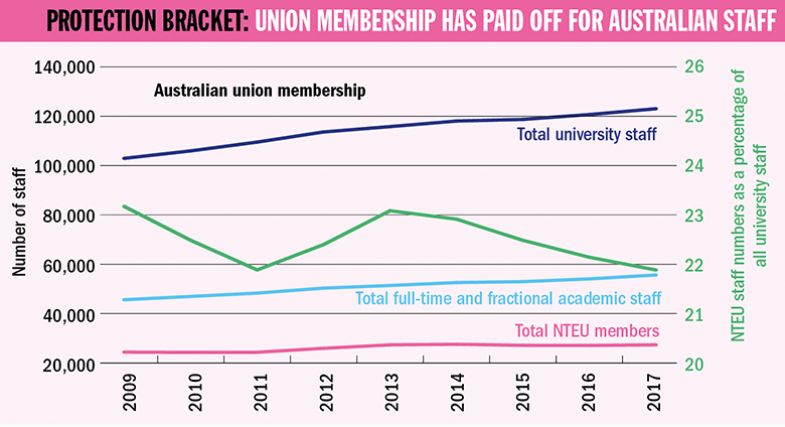

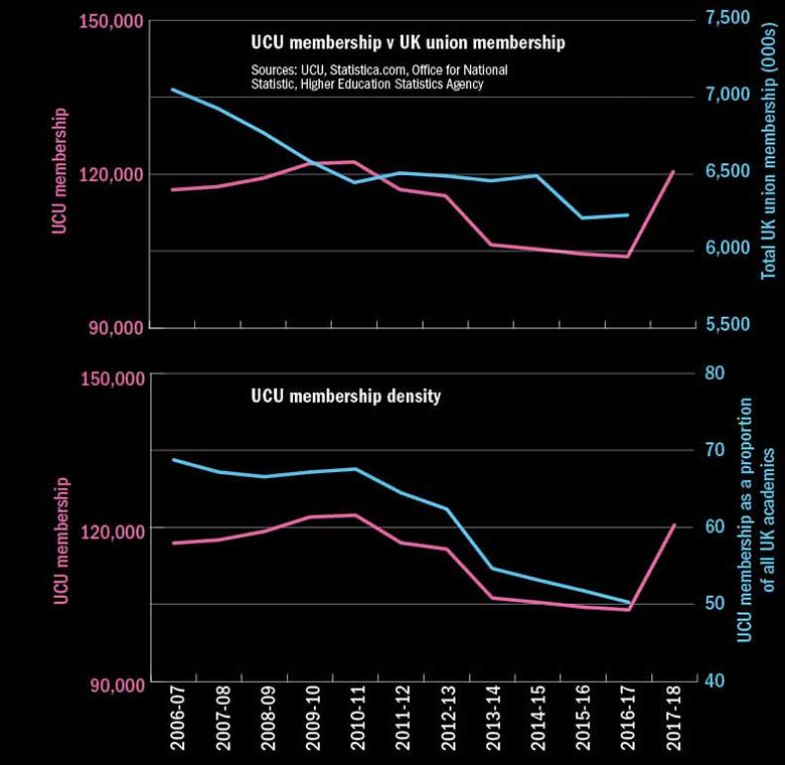

Changing fortunes: UCU membership compared with union membership in the UK overall

Other UCU veterans are not so sure that the new grass roots movements are as non-partisan as they claim. Terry Murphy, chair of Teesside University’s UCU branch, sees them to some extent as a mere “repackaging” of UCU Left, the hardline socialist group that, for years, has battled for control of the union with Hunt’s more centrist Independent Broad Left alliance. He adds that those pushing for a more hard-line approach to pension negotiations and industrial relations more widely are not in step with the broader UCU membership. And while he recognises the good work done by UCU Left activists in local branches, Murphy thinks that their vision of “opposing neoliberalism in every form” and fighting every less-than-perfect management proposal is unrealistic.

“It’s not defeatist to say that organising a strike is very hard,” he says, adding that he “does not see how a revolutionary agenda fits with the complexities of modern higher education”.

In the case of the pension dispute, those who argued to reject the UUK offer and continue the strike ignored the financial pain felt by many UCU members, he says. “A lot of people who came on strike were not actually that affected by the changes,” says Murphy, referring to older academics who had already banked decades of contributions under the final salary scheme that closed in 2016. “You have to make a judgement about how long those people will accept major losses for very little gain, especially when they have mortgages to pay,” he says.

“It is sometimes difficult to know when a win presents itself – do you take 90 per cent of what you wanted or hold out for everything?” he says. But his view is that the creation of an expert panel to review the case for moving to defined contributions – which has subsequently recommended far less brutal cuts – counted as “success”.

It is also possible that the “small but significant number [of activists] who have a more revolutionary political agenda” and who, according to Murphy, “take a disproportionate position in union branches” and dominate congress proceedings turn more moderate academics off unionisation. However, the recent spike in membership means that the union now has more members than it did when it was formed in 2006 out of a merger of two predecessors, reversing a previously downward trend that mirrored a general decline in union membership across the UK economy (see graphs).

Last week, Hunt announced that she was taking a break from the UCU after doctors warned her that the “very high” pressure of the past year risked worsening her multiple sclerosis.

In the US, a different type of grass-roots activism is on the rise. Thousands of staff on non-permanent contracts – the “academic precariat”, who often have no job security, no benefits and low wages – have started to unionise. According to research conducted by the Delphi Project on Changing Faculty and Student Success, more than 60 campuses have organised with the Service Employees International Union, with 20 new faculty unions certified in the first three-quarters of 2016. This has, in turn, led to better pay and conditions, according to a Chronicle of Higher Education analysis published in June. Of 35 institutions where collective bargaining agreements were ratified between 2010 and 2016, all adjunct faculty won salary increases, some of which were substantial. Adjuncts at Boston University, for instance, enjoyed rises of between 29 per cent and 68 per cent over a three-year period. Many union members also gained access to professional development funds.

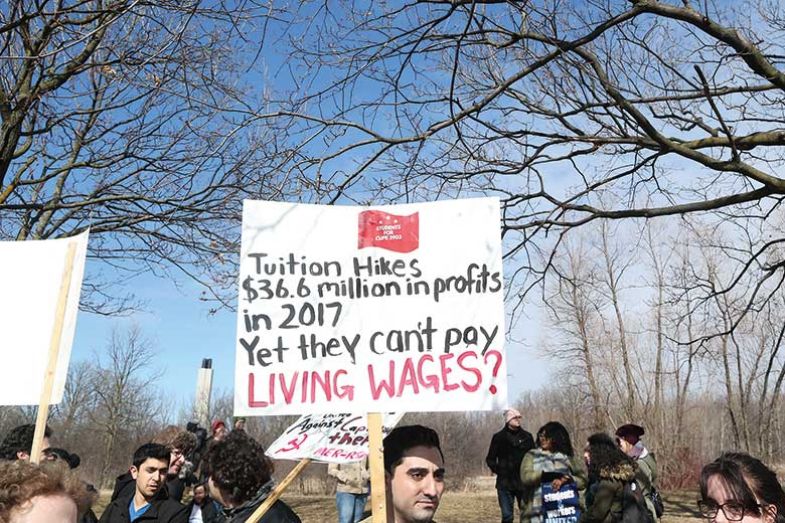

Meanwhile, in Toronto, the York University branch of the Canadian Union of Public Employees called the longest strike in an anglophone Canadian university earlier this year. The four-month walkout by casual staff (pictured below) in protest at job insecurity was only ended by legislation by the Ontario government ordering a return to work.

And, last week, 2,000 doctoral researchers at Columbia University voted to unionise with the United Automobile Workers union, in what was billed as the first union contract covering postdocs at a private US university.

Attempts by graduate student workers to form their own unions are particularly high profile, with PhD students at at least 14 different US institutions voting to unionise over the past 18 months, according to the Chronicle. Harvard University is the latest employer to recognise such a union, having previously insisted that its 5,000 graduate student teachers are students, not employees.

Sheffield’s Fox-Hodess, a former chair of the teaching assistants’ union at the University of California, Berkeley, believes that the rise of graduate student unionisation is part of a wider movement among millennials. “Most of those engaged are younger people who have entered the labour force during the economic crisis and seen fewer opportunities to progress,” she explains. “People used to expect getting a PhD to be a path to economic security, but that is no longer the case. This is also a new era of social struggle, as seen with the Occupy movement, #MeToo and Black Lives Matter, and this is big part of what’s happening.”

More Ivy League universities may now follow Harvard’s move, which was announced in May. “This really is a movement and we’ve learned a lot from other graduate students who have unionised,” Justin Bloesch, a Harvard PhD student in economics, tells THE. While the need to improve salary and benefits has been an important driver, he emphasises that it is not the only one. “Financial issues can be deeply felt but some graduate students wanted a union for protection against potential sexual harassment and the fact that our academic careers are hugely dependent on one person,” he says, adding that “discrimination can be worse for us than other faculty” given graduate students’ lack of power.

But it remains to be seen whether graduate unions can continue to flourish beyond the departure of their original founders, at the end of their periods of study.

“That is always the challenge about organising students,” Bloesch concedes. “But the union is a very good way to do this [since it] creates a sense of continuity on key issues thanks to its structure.” Moreover, the “sociable nature of graduate student life” also offers distinct advantages. “We are always having these in-depth conversations about how people are working and how they might improve it.” More senior research staff, by contrast, are “always in the lab and do not talk to each other as much”, Bloesch argues.

Graduate student unionisation has long been legal and recognised at state universities, but its spread into private institutions represents an exciting development for the US trade union movement, according to William B. Gould, emeritus law professor at Stanford University and chairman during the Clinton presidency of the National Labor Relations Board, the body responsible for overseeing elections in which workers decide to form a union and for investigating unfair labour practices.

“Numerically, the numbers are small, but these new bodies are bringing a new creativity and energy to our trade union movement,” says Gould, noting that unions formed during the Great Depression eventually became the mainstays of employee representation. He particularly admires the way that groups representing graduate teaching assistants (GTAs) at universities that have resisted recognition – such as those at Columbia, Yale, Boston College and the University of Chicago – have adapted to a labour relations board whose budget has been cut by Donald Trump and whose membership is now dominated by his anti-union appointees.

“The Obama board’s decision in 2016 in the case of Columbia held that graduate students are employees in the eyes of the law, and it was a great shot in the arm. But the Trump-era board is looking to reverse Columbia,” explains Gould. In response, instead of filing appeals to the board in the way they previously did, nascent GTS unions have instead sought to deal solely with universities, using pressure from major US unions to compel them to recognise collective bargaining.

Trump has also given a 20 per cent funding boost to the union watchdog, the Department of Labor’s Office of Labor-Management Standards, while the vote of his arch-conservative Supreme Court appointee Neil Gorsuch was crucial in the landmark case of Mark Janus, who successfully argued that he should not be forced to pay dues to the union that represents employees at his workplace. In its June judgment, the court explained that this arrangement “violate[s] the free-speech rights of non-members by compelling them to subsidise private speech on matters of substantial public concern” – a ruling that was described as “part of a broad assault on public institutions and the common good” by the American Association of University Professors (AAUP).

“It is already having a major impact,” says Gould. “Some employers, at the behest of organisations like [anti-union body] the National Right to Work Committee, are requiring employees to affirmatively express their allegiance to a union and whether they are willing for union dues to be collected,” he explains. The issue of “free riders” will soon become a problem for union membership, adds Gould. “Workers who might not pay dues will enjoy the same benefits as union members who do, so some might think: ‘Why should I have to pay dues when other guys are getting the same benefits without paying anything?’ ” he explains.

At Rutgers University’s AAUP-American Federation of Teachers branch, the loss of non-union dues – set at 85 per cent of the amount paid by members and known as “fair share fees” – is likely to account for about a quarter of its operating budget, says David M. Hughes, the branch’s vice-president. A small number of non-unionised faculty have signed up following the ruling, recognising their iniquitous position of “enjoying the benefits of unions but not paying anything towards their work”, he says. However, the blow imposed by the Janus ruling is not merely financial: unions have also been weakened by the dilution of the “political” support that they tacitly received from non-members. “We need their political support more than we need the money,” says Hughes.

Gould notes that the Supreme Court has suggested that unions charge individuals for the costs of carrying out certain tasks, such as handling workplace grievances or tribunal advocacy. “But the problem is the union system requires everyone to pay into the system year-round, not just when specific issues arise,” he says. “Like healthcare, if you don’t have insurance and only pay in when problems happen, the costs are massive.” The defunding of academic trade unions as a result of the Janus case may also limit the grievance cases that unions pursue, he adds. “A single day in arbitration can cost up to $20,000, so who will pay that if unions don’t take it on?”

Another Supreme Court ruling from earlier this year restricts the ability of workers to be included in class action lawsuits, putting up a further barrier to employee representation. “The Supreme Court has not been that hospitable to organised labour over the past 30 years, but it has ramped up the degree of hostility in recent months with this double-barrelled attack on unions,” concludes Gould.

Rutgers’ union density remains strong, with some 72 per cent of faculty signed up. “That’s high for a research-orientated institution, but it would be low for a teaching-focused university,” says Hughes. That difference in unionisation is the result of the fact that “researchers see themselves as managers of their own projects, rather than as workers”, he says.

Fox-Hodess, however, rejects the notion that academics are inherently averse to joining a union given the high levels of autonomy that most enjoy in their careers. “What matters is the kinds of union available. Are they participatory? Do members have a say in their direction? Are their voices heard? If they are, then people will get involved, no matter how much money they make,” she says.

Either way, union solidarity has delivered some impressive results for staff, particularly more junior colleagues, Hughes says.

“We won an 8-9 per cent pay rise for tenure-track staff over a four-year period, but we won a 40 per cent rise for non-tenure-track faculty. Winning on this agenda is vital for a larger fight against the marketisation of higher education. We cannot campaign on this unless academics have reasonable security and working conditions.”

Trade unionists in Australia also complain of having to swim against the legislative tide. Industry-wide bargaining, as found in the UK, was scrapped in the early 1990s in favour of “enterprise-level” bargaining between unions and specific employers. And industrial action has been banned outside the official pay bargaining window. This “only occurs every three to four years, so it’s impossible to strike most of the time”, says Jeannie Rea, president of the National Tertiary Education Union – the country’s main union for university staff – for the past eight years. Moreover, the balloting process for authorising strike action during the brief windows is “ludicrously complex”, requiring union branches to outline exactly what action they wish to take and when.

“In the old days you could pull people off the job to protest public spending cuts and you might even get support from vice-chancellors, but management is a lot more antagonistic and aggressive these days,” Rea says. However, NTEU membership has held up over the years at about 27,000 of Australia’s 120,000 university staff. And such solidarity, according to Rea, has helped to win considerable improvements to Australian academics’ perks, such as maternity pay of up to 36 weeks at many institutions, and to obtain salary settlements that are among the best in the world.

According to a recent NTEU pay survey, professors in Australia earn an average of between A$168,000 (£91,830) and $194,000 (£106,000) a year, and lecturers are on between $91,000 (£49,740) and $121,000 (£66,140).

One of the reasons for the NTEU’s success is that, unlike the UCU, it is “remarkably factionless”, says John O’Brien, honorary associate professor of work and organisational studies at the University of Sydney, whose 2015 book A Most Unlikely Union traces the NTEU’s history over the past two decades. “There are a few Trotskyites, but they are usually tamed when they win elected positions,” he says, adding that politicians of all stripes have felt able to engage with the union over the years.

“Someone from the government usually speaks at the NTEU’s annual conference,” O’Brien says: a scenario unimaginable in the UK. “When Brendan Nelson was education minister for the [centre-right] Liberals, he came to conference and ended up delivering some big bonuses for higher education, albeit tied to tighter regulation,” he recalls.

O’Brien credits much of the union’s progress to its branches in high-profile “pace-setter” institutions. Their ability to win key concessions helps other unions to demand the same thing for their institution, he explains.

One such institution is the University of Sydney, whose status as the country’s oldest university guarantees it a disproportionate level of public attention, with events on campus frequently reported in the media. However, gains are still not easily won, according to Nick Riemer, an NTEU activist at Sydney.

“The strength of the branch is a result of everyone’s commitment to maintaining a constant visibility at the university – frequent members’ meetings, a regular union presence in the workplace, members frequently handing out leaflets to staff coming in to work in the morning, a constant programme of campaign actions, even including regular demonstrations. We also work closely with student organisations,” says Riemer, who is a senior lecturer in the School of Literature, Arts and Media.

Successes also have to be set against what Rea admits is the union’s “limited” capacity to combat the “catastrophe of casualisation”. According to a recent report by the Grattan Institute, an independent thinktank, some 94,500 people are employed on a casual basis at Australian universities, predominantly in teaching roles, with the share of full-time equivalent academic staff on insecure contracts rising from 14 per cent in 1989 to 23 per cent in 2016 – and reaching more than 50 per cent in headcount terms.

“We’ve been trying to get clauses that convert temporary contracts into permanent ones or encourage the creation of jobs that lead to more regular teaching and research roles,” says Rea. But she notes that it is an uphill task: “We have people who been with the same university for 20 years, winning promotion to professor, but [who] still can’t get a permanent job,” she says. In THE’s recent survey of university leaders, 69 per cent of Australian vice-chancellors expect casualisation to continue to increase between now and 2030, while just 8 per cent do not.

Part of that expectation relates to the “fourth industrial revolution” of robotics and artificial intelligence, which could have a drastic effect on the graduate employment market – and, therefore, on the demand for degrees. Moreover, casualisation is a phenomenon that is on the rise across economies, at a time when right-wing politicians, who are generally sceptical of unions, hold most of the levers of power.

In the face of such large-scale social trends, it remains to be seen whether the apparent rise in grass-roots activism at anglophone universities will be enough to keep the state of their unions strong.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: The state of the union

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login