Why is there so little collaboration between universities across Latin America? The answer, according to one scholar, is down to geographical divisions, cultural differences and mutual dislike between the countries that “started in the 15th century”.

Fredric Michael Litto, president of the Brazilian Association for Distance Education, told Times Higher Education that although there are “a lot of agreements on paper” between institutions in Brazil and the region’s Spanish-speaking countries, “effectively very little is done” in the way of research or academic partnerships.

The reasons for this extend beyond language differences, he said, adding that there was also little collaboration between the Spanish-speaking countries, which tend to “look more to Spain” for partnerships “than to each other”.

The “first major dividing point” between Brazil and its regional neighbours, he said, harks back to 1494 and the Treaty of Tordesillas, which divided the recently discovered lands of the New World between Portugal and Spain.

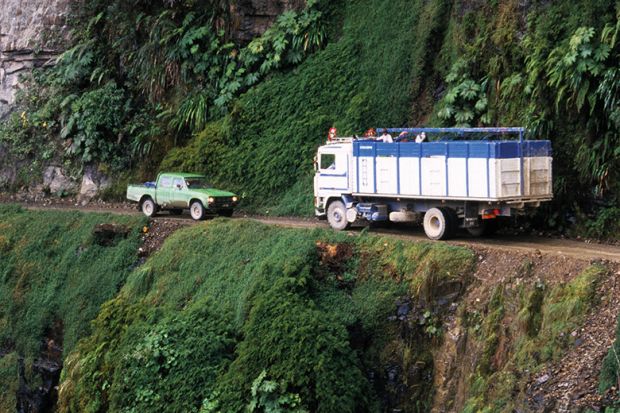

There is also the formidable physical barrier of the Andes mountain range, which has made transport difficult and has long hindered contact between populations in the western part of South America and Brazil, he added.

Cultural differences have hampered cooperation as well, Professor Litto said. The Hispanic region of Latin America started to build universities in the 16th century, but Brazil’s first, the University of São Paulo, was not founded until 1934 because the Portuguese monarchy feared that universities were “dangerous places” where people might plot a “revolution”.

Another potential reason he cited is that the other countries in South America have an “inbred fear of Brazil’s gigantic size and growth”, given that the country accounts for half the continent’s land mass as well as half its population, and that Portuguese Catholicism is traditionally “lighter” than Spanish Catholicism.

The combination of these factors means that university partnerships between Brazil and the Spanish-speaking nations are “not strong”, Professor Litto said.

He also noted that the former Spanish colonies had been left in “disarray” after the decline of the Spanish empire, which led to much “hate and fighting” among them that continues to this day.

“Argentina and Chile are mortal enemies and have been for centuries. Venezuela and Colombia [are] also,” Professor Litto said.

“So partnership [between] universities [in those countries] for research projects is more on paper than it is actually realised.”

He said that Brazilian universities have recently started to focus on increasing international links, prompted by calls from the government to improve their performance in global rankings.

However, while he admitted that greater collaboration across Latin America would “probably improve the quality” of research, Professor Litto predicted that this was unlikely to occur any time soon.

“They’re still warring with each other over territorial disputes in the north [of South America],” he said.

“I really don’t see any change either in Brazil or in the Spanish-speaking countries over these tendencies.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login