Universities may have a lingering reputation for being ivory towers with little direct intellectual or practical links to the “outside world”. But in reality, the so-called refugee crisis offers up a number of significant opportunities and challenges to European higher education. The largest mass movement of people since the end of the Second World War opens vast research opportunities for those studying migration and integration, and the arrival from the Middle East and North Africa of huge numbers of young people thirsty for higher education could significantly boost student numbers in their host countries.

But catering for such large cohorts will obviously bring its own challenges – not least over the extent to which normal admission standards should be relaxed, and whether institutions should offer dedicated practical and financial support to refugee applicants.

Then there is the question of whether Western universities can make room on their payrolls for academic refugees from Syria, forced out of their own institutions by the country’s catastrophic war.

Here, we examine the admissions conundrums and hear a range of personal perspectives from those affected by the crisis – victims, researchers and an activist. It is clear that many academics and universities are putting significant time and resources into responding to the crisis, but, as in all emergencies, the question will always remain: is it enough?

Doors are opening, but bureaucracy and funding problems must be overcome

“Life is not easy for me now, but I still have the zeal to study so that my future is brighter,” says Michael Yeboah.

The 25-year-old Ghanaian has been sleeping rough in Hamburg for several weeks after enduring a miserable few months drifting between European countries looking for work.

Yeboah left his homeland to study in Ukraine, but lack of funds meant that he had to quit the country before completing his degree. He believes that he has the qualifications and the ability to study in Germany, but has no idea of where to start his search for a university place.

Yeboah, who contacted Times Higher Education seeking advice after he read a story on migrant qualifications, is just one of the 800,000 people expected to arrive in Germany this year with the aim of applying for asylum.

In addition to the millions fleeing Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, a substantial number of migrants are leaving Africa: the number of asylum applications from the west of the continent is just as high as those from the violent, ungoverned states further east, such as Libya and Somalia, according to latest United Nations figures.

With between 8,000 and 10,000 migrants arriving in Germany daily at certain points, the inflow of newcomers has placed a huge financial strain on the local governments faced with housing them. The influx – welcomed by the country’s chancellor, Angela Merkel – is also set to place a sizeable burden on Germany’s universities as the incomers seek the qualifications necessary to gain a foothold in the national labour market.

“We think there are between 30,000 and 50,000 [migrants] in 2015 who may be interested in studying [in Germany],” says Stefan Hase-Bergen, head of the marketing division of the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD). “Many German universities have already started measures to integrate refugee students into university courses. They are willing to do as much as they can to help, but they need more money and [support] to provide the right services.”

Refugees keen on study will need clear information on the German university system, extra language classes, checks on their credentials and help with their applications, in addition to financial assistance with housing and living costs, he explains.

“There is also the psychological dimension to consider, as these people have left their homes in Syria and Iraq,” he says, suggesting that they might need counselling.

Universities eager to accept refugee students may also need to become more flexible on admissions, introducing bespoke testing for applicants whose education may have been interrupted by their flight across Europe, Hase-Bergen adds. The problem is that many European states have very rigid and legally binding centralised undergraduate admissions systems, based on a single set of national exams. In the Netherlands, for instance, very few university programmes are allowed to interview applicants because this is viewed as giving more privileged students an unfair advantage.

“Universities are trying to act with more flexibility, but [an applicant] must have the capability to be a successful student,” says Hase-Bergen. However, he adds: “We see this as a great opportunity to enrol students with a lot of potential.”

Indeed, many university staff have been impressed by the quality of some of the Syrians seeking study opportunities.

“The Syrian people are very well-educated,” says Fahri Yavuz, head of the Office of International Affairs at Atatürk University, a large public university in Erzurum, eastern Turkey, which has accepted 150 Syrian students this autumn, up from just 10 last year.

“They have come from Aleppo, Damascus and other cities famous for their culture, so it is not unexpected,” says Yavuz, who points out that Turkish universities will admit more than 5,000 refugee students this year, funded out of Turkey’s $6.5 billion (£4.3 billion) annual spending on humanitarian relief for Syrian refugees.

Enrolment numbers are far smaller in most European states but are nonetheless considerable. In Sweden, another popular destination for refugees, the number of people seeking recognition of higher education credentials was 6,255 in the first nine months of 2015: almost double the number three years ago, according to the Swedish Council for Higher Education. Of those making enquiries, 1,636 were Syrians, up from just 47 in 2012.

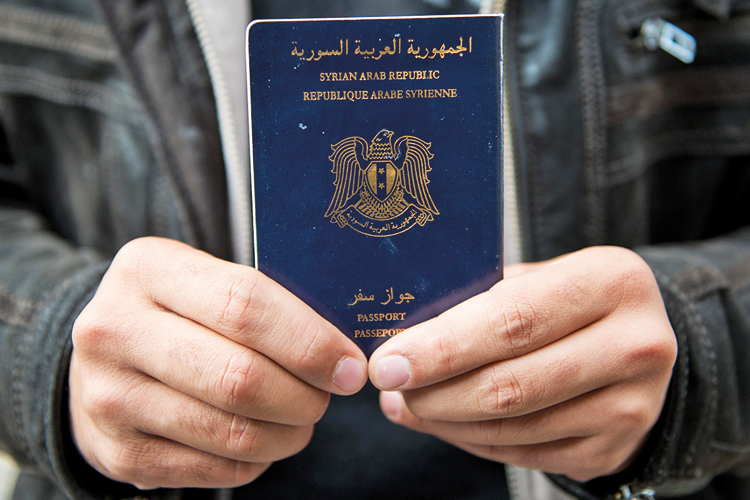

Under the Lisbon Convention signed by all European Union member states in 1997, countries must make an effort to establish a system in which credentials of displaced people can be verified. But many refugees are arriving in European countries with no documentation, explains Stig Arne Skjerven, director of foreign education at the Norwegian Agency for Quality Assurance in Education (Nokut).

“It might not have been possible for them to obtain their educational credentials before they left, or they might have been lost on their journey. [Even] when they do have qualifications, it is not always possible to verify some documents,” Skjerven says. That is particularly true of qualifications from Iraqi universities – which is why the agency does not deem them sufficient for university admission or professional accreditation in Norway.

Checking legitimate documents can also be time-consuming, costly and sometimes impossible when they are held at universities blighted by war or in countries where university systems are corrupt or substandard. In those cases, subject-specific testing procedures must be designed, but this is also costly at about €5,000 (£3,700) per applicant, Skjerven says.

The process of verifying refugee qualifications is particularly onerous and ineffective when it is farmed out to individual institutions, as it was in Norway before 2012. Since then, Nokut has assessed the competencies of about 250 refugees, including engineers, chemists, biologists, accountants and mathematicians, and half of them are now in work or further study.

Skjerven advocates the adoption of a similar centralised programme at a continent-wide level because migrants are likely to move between different EU member states.

“This is a huge European crisis, and it clearly requires some kind of extraordinary coordinated action from the European Commission to address the imminent challenge,” he says.

Jack Grove, Times Higher Education reporter

Individual institutions: Finding ways and means to help

Universities in Munich, where thousands of migrants are arriving daily, are adopting special measures to cater for those seeking higher education. LMU Munich has set up a dedicated programme to prepare refugees for regular study, and is offering free courses in German. Meanwhile, the Technical University of Munich will permit refugees who had started or were about to start university courses in their own countries to sit in on course modules from this semester, so as to familiarise themselves with the German higher education system. They will also be helped by student mentors, in preparation for applying for a regular place on a TUM programme from 2016.

Meanwhile, the European Commission has launched an initiative called science4refugees to match refugees and asylum seekers who have a scientific background with scientific institutions prepared to offer them positions, internships or training.

In the UK, several universities have announced plans to fund places for refugees – mostly those already in the UK. The University of Warwick is to offer 10 student scholarships for this academic year, and another 10 for 2016-17, with the majority likely to be for postgraduates.

The University of York has set up a three-year package of initiatives, worth £500,000, which will offer financial support for three undergraduates a year. Scholarships of between £23,000 and £28,000 will be awarded from 2016. York will also welcome two refugee scholars to its campus, at a cost of almost £200,000 over three years, and staff will be encouraged to contribute towards a “give as you earn” scheme to support its scholarship fund.

The London School of Economics is also to commit nearly £500,000 a year to help students seeking asylum. This will provide three undergraduate scholarships, covering annual tuition fees and paying living costs of £11,000 a year from 2016, while 10 awards for postgraduates, worth up to £40,000 a year depending on the course, will also be provided. The LSE’s Institute of Global Affairs is also working with the institution’s scholars to develop policies to tackle the refugee crisis, and will host a series of events on migration for students, policymakers and the general public.

The University of Glasgow has so far taken in two Syrian academics as PhD students. It has also announced measures to support refugee students who have settled in the UK, including offering fee waivers and access to scholarship schemes.

Syrian refugees who have temporarily settled in Jordan and Lebanon are being taught by the Open University in partnership with the British Council. The council, which is teaching English, French and German to about 3,000 inhabitants of the refugee camps, will select 300 of the most talented students to take an online degree course accredited by the OU. Some 400 other students will also have the chance to take a short online course on the OU’s learning platform, FutureLearn.

The University of East London has committed to funding 10 postgraduate scholarships to Syrians in refugee camps, 20,000 of whom will be permitted to come to the UK over the next five years.

Meanwhile, the Campaign for the Public University has written to Universities UK calling for every UK university to offer at least five scholarships and bursaries for those fleeing violence or persecution. It also calls on universities to improve their links with the Council for At-Risk Academics (Cara). The organisation says that it is currently in touch with more than 100 overseas academics in imminent danger, the majority of whom are Syrians.

Jack Grove

The activist: Meeting human need is at the heart of social work. That is what we must do

At the start of the summer, Britain’s prime minister talked about refugees in the most disparaging terms. They were a “swarm of people coming across the Mediterranean, seeking a better life”. The majority of the tabloid press were even more hostile, and the government committed to building a new fence near the Channel Tunnel in Calais to keep the refugees out.

But as the images of poor and desperate people fleeing civil war and the destruction of their homes and cities started to dominate our television screens, the popular mood began to shift – especially after the terrible pictures emerged of the drowned three-year-old Aylan Kurdi, washed up on a beach. Refugee support networks sprang up across Europe. Local communities, trade unions and activist groups organised to send food and money to refugees at hotspots. The key question became: what are you going to do?

Social work is guided by an international definition as to its values, ethos, duties and activities. This talks about a commitment to universal human rights, human emancipation, social justice and meeting human need. If this is how social work self-defines, how could it not speak out in support of refugee rights?

As national coordinator of the Social Work Action Network, I felt it was time that my profession and academic discipline made a stand. At the beginning of September, the network – a campaigning group of social work practitioners, academics, students and service users – announced that we would organise a convoy to Calais on 17 October to take food and supplies to the refugees living in the “Jungle”.

The convoy has grown beyond all initial expectations, with cars, vans and lorries travelling from all over the country. A container of goods is also being sent to the Greek island of Samos, where a former social work professor from the University of Liverpool, Chris Jones, has established a refugee support network.

In Calais, we will also be announcing the creation of a cross-European Social Work Refugee Support Network with the European Association of Schools of Social Work. For us, offering solidarity and engaged political support to vulnerable people is also about re-establishing a forgotten tradition within our discipline. In the 1930s, social workers spoke out and supported refugees fleeing fascism in Spain and Nazism in Poland. We, as academics and practitioners, want to reconnect with that history and re-establish a social work that puts people first – no matter where they come from.

Michael Lavalette is professor of social work and social policy and head of the department of social work, care and justice at Liverpool Hope University.

The refugee: Many of my relatives were killed. Nobody could leave their house after sunset

I am an assistant professor from a university in Syria. After getting my PhD in Europe, I returned to do my duty as an academic woman and a scientific researcher to participate in my homeland’s development, and to transfer to my students the experience I had gained.

However, a few months after I returned, the conflict started. Safety and stability were lost. Water, electricity, fuel, telecommunications and transport all became scarce. The spectre of death was everywhere. In these circumstances, it became impossible to pursue academic work and research. My master’s students stopped coming to classes. All my hopes for contributing to Syria’s future were dashed, and my dominant feelings were despair and loss.

When the conflict reached our neighbourhood, we lost our homes and were forced to move to the countryside. It was very difficult to travel because of the hundreds of security and military checkpoints and the arbitrary arrests. Psychologically, I was completely broken. I stayed with my family for nearly two months. Many of my relatives were killed by rockets, snipers and explosives. Nobody could leave their house after sunset. Basic services were now completely absent; even baby milk was unavailable. Most schools were crowded with people who had lost their homes or had moved to find security. Many teachers had stopped working because their salaries were no longer being paid. Students lost years of education, and their futures with it.

A few months later, Islamic State came on to the scene: groups of strangers who had “immigrated” to Syria to practise terrorism under the name of Islam. Unimaginable crimes have been committed against civilians. They slaughter and crucify; they whip men and rape women. Life became impossible, and we were forced to leave (in very difficult circumstances) and go to a neighbouring country. We faced many difficulties, as Syrians, around getting permission to stay. We were treated badly. Nights were dark, long and full of tears.

Fortunately, I heard about the Council for At-Risk Academics (Cara), which helps academics affected by war to find a position in European universities. I am very grateful for all the assistance and solidarity I received from its staff. Within six months, they were able to provide me with an opportunity to pursue my research in one of the most advanced and prestigious scientific universities in the world.

It is not just a Syrian dream that this tragic war will come to an end. Peace is what we all need. Only that will make it possible for us to go back to our homeland and to start again to rebuild it.

The author wishes to remain anonymous.

The doctors: As things have changed, so have our roles as researcher-clinicians

Since the Balkan wars in the 1990s, refugees from nearby war zones have been coming to us in Germany on a more or less steady basis. As clinicians and researchers from two centres for child health and child psychiatry at the Technical University of Munich, we were interested in studying the effects of war and terror on them.

A project funded by a foundation for child health was started at a time when refugee numbers were still moderate. In 2014, our team examined 102 children and adolescents from Syrian families living in a large refugee camp in Munich. The research method was simple and descriptive: paediatric examination, diagnostic interview and standardised testing for possible mental disorders, plus interview about their experiences in their home country, during their journey and in Germany. Language and cultural barriers were not easily overcome even with a translator, and there were worries that the interviewees might be harmed by being asked to relive their experiences.

Nevertheless, the results were clear and important. Almost all children and adolescents had experienced traumatic events, defined as having induced feelings of terror and intense helplessness, with about one in five showing symptoms of full-blown post-traumatic stress disorder. Other refugee children suffered from severe respiratory and other infections, and even cancer.

As well as assessing the children, we offered integrated psychiatric care for as many unattended adolescents among the refugees as we could afford to see in addition to our usual patient load. In all this, we were still in essence functioning in the standard, dispassionate academic mode, writing up the results of our study, presenting them at conferences and making recommendations.

But recently, things have changed dramatically – and so have our roles as researcher-clinicians. Many hundreds and often many thousands of refugees have been arriving in Munich every single day since late August. Many of us are engaged personally in helping both the refugees themselves and the Munich authorities, who are extremely supportive but are overloaded. Some of us work as voluntary doctors directly at the main railway station where the refugees arrive; others provide shelter or organise donations of food and clothes.

Many interesting research questions were raised by our initial study, such as what the risk and protective factors are for developing PTSD in this specific context, but the current crisis means that there is no time to plan and perform regular research of this type just now. Instead, we do things that we usually consider to be of second priority for academic researchers, such as campaigning via the media for more attention to be paid to refugees’ mental health problems; networking with other Munich institutions to develop low-level stepped care models for refugees using best available evidence; and, very importantly, developing training models for the many social workers and helpers in direct contact with the refugees, who are often distressed and, hence, “difficult”.

As there is no indication that the refugee crisis will end soon, we will be challenged to find ways of combining this engagé approach to academic medicine with the standard, dispassionate one – helping and investigating how best to help at the same time.

Peter Henningsen is dean of the School of Medicine at the Technical University of Munich and director of the department of psychosomatic medicine and psychotherapy at TUM University Hospitals; Sigrid Aberl is a senior physician in child and adolescent psychiatry and psychotherapy in the department; and Volker Mall is professor of social paediatrics at TUM.

The exile: The response has been inadequate. We need real will, and plans of action

The other day, I was watching a Sky News interview with a mother from Syria. She was stuck at the Hungarian-Serbian border with her husband and her six-year-old daughter. She told the presenter: “All [the migrants] want to go [to Europe] for their kids, not themselves. OK, take our kids to Germany. No problem, and I will come back to Syria. My right to live a safe life, I don’t want this right. I want this for my kid. To go to school. It’s a simple right.”

Education is important to the Syrian middle class. Since its establishment in 1918, Syria has witnessed an increasing rate of literacy, with a reasonable education system furnished with free public schools and universities. However, the Syrian authorities have treated the system as a tool for supplying bureaucrats and technicians, rather than for enriching research, critical thinking and intellectual life. This “utilitarian” approach became more prominent when the Baath Party took over in 1963, suppressing freedom of speech, imposing ideological constraints on the social sciences and humanities and using schools and universities to distribute its propaganda.

In the early 2000s, reforms including better stipends for academics and increased research funding were introduced to higher education. Back then, I was an assistant lecturer at the University of Aleppo. While spending time in the UK working for my PhD, I contributed to establishing a cancer research unit in Aleppo in 2011. But the enthusiasm over its launch was mixed with a feeling that the project was unsustainable because the reforms of which it was a product were only partial and ignored the constraints imposed on Syrian society by despotism.

The crisis in Syria, which began that same year, has led to an estimated 250,000 deaths and 12 million people displaced. Inevitably, academia and education are among the sectors torn apart. Scientific research, including the cancer unit, which fell apart in 2012, has become an unthinkable luxury. Staff and students have been trapped by the violence, and many have fled because of direct or indirect threats to their lives. I myself received such threats, leading to my decision in 2012 to settle in the UK.

The world’s response to the Syrian crisis has been inadequate, disorganised and unsustainable. The UK can and should do more. It has the resources, the moral responsibility and a history of welcoming refugees. It can also support peace projects, lead research into the crisis and push for solutions to be found. UK universities can play an important role by offering scholarships and fellowships to support Syrian scholars and graduates. They could set up joint programmes with universities in Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan, and contribute to temporary university campuses there for Syrian refugees. What is needed is real will, and plans of action.

It is a pity that humans haven’t developed ways of settling conflicts without resort to war and destruction. However, instead of succumbing to pessimism, we should cling to our belief in the essential goodness of humankind. Perhaps then, the ever-growing Syrian diaspora, including academic expats like me, might have a chance one day to see our homeland again.

Talal Al-Mayhani is a researcher in the department of clinical neurosciences at the University of Cambridge, and serves as director of the Centre for Thought and Public Affairs.

The expert: I have a duty to share my work on migration. But high demand for it can be stressful

As an academic studying migration, the current crisis is both a big opportunity and a huge burden. It was advocacy that led me into the academy. As a student in Germany in the 1980s, I used to help foreign students through the system. After graduating, I moved into social work with asylum seekers, and then into another post concerned with healthcare for immigrants. I did quite a bit of lobbying, which required some research to support our arguments. After that, I worked for a while as editor of a development policy magazine before going back to university for a PhD and finally becoming an academic. In search of academic opportunities, I became a migrant myself.

I have recently been to Ankara to complete a technical assistance project for the Turkish government on the future of the 2 million or so Syrian refugees in Turkey (it is an open question whether the Turkish government is ready to admit that many will remain permanently). From there, I rushed to a migration policy laboratory with Greek officials to reflect on the challenges of the crisis for a European Union border country. And with partners, my research team has just won one of the Economic and Social Research Council’s urgency grants to study the crisis in the Mediterranean, which will allow me to gather first-hand insights from many crucial sites, such as Lesbos, İzmir, Istanbul, Athens and Macedonia.

Conducting such research comes with the responsibility to report back to stakeholders and society. But high demand for dissemination and media requests can be stressful: my record for media interviews is seven in one day. This year, I have already spoken about the refugee crisis at the Council of Europe, the House of Lords and a thinktank in Ankara, and I am invited to the United Nations’ Global Forum on Migration and Development and the Médecins Sans Frontières annual conference. But the demand for my knowledge and advice gives me the feeling that what I do is relevant.

I also do what I can to support the vital work on the ground. For instance, I’m on the executive committee of the Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrants, a Brussels-based umbrella organisation that lobbies for migrants’ human rights. Attending the annual conferences is like feeling the heartbeat of civil society.

In my teaching, I feed back my previous social work experiences, my ongoing engagement with stakeholders and fresh findings from research, and combine this with the analytical and theoretical dimension. I encourage my students not to move straight from MA to PhD, but to work in the field and get some real-life experience. And I encourage those who become practitioners to keep their analytical glasses on.

Instead of agreeing to act as auxiliary immigration officers for the Home Office, UK universities should waive fees for refugee students, like Turkey does for Syrians, and fund staff to go abroad on teaching stints, so that students in other countries can benefit from our accumulated wealth of knowledge. That would be the kind of migration from which everyone could benefit.

Franck Düvell is an associate professor and senior researcher at the Centre on Migration, Policy, and Society, University of Oxford.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Havens, hopes and hurdles

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login