In a recent radio item on the Campus and Karriere programme of German public radio station Deutschlandfunk, the point was made that people are studying German less for the literature and more to improve their career prospects. Academic interest in Goethe, Schiller and so on – the “klassische Germanistik” – is declining.

There is evidence that businesspeople can earn more if they have good German skills. While such gains are not always substantial, a lot depends on the individual. In some cases, proficiency in German (and other languages of course) or the lack thereof can make or break a career. This burgeoning interest is mainly from Eastern Europe and developing countries, very much including China – and not from the UK.

Through my own interest in the language, I was well aware of these issues in the 1990s and did some “business German” teaching for commerce and arts students. Unfortunately, the literature academics were reluctant to support any concerted initiative, as they presumably saw it as a threat to their traditional courses. They would agree only to a peripheral course outside the main degree programme.

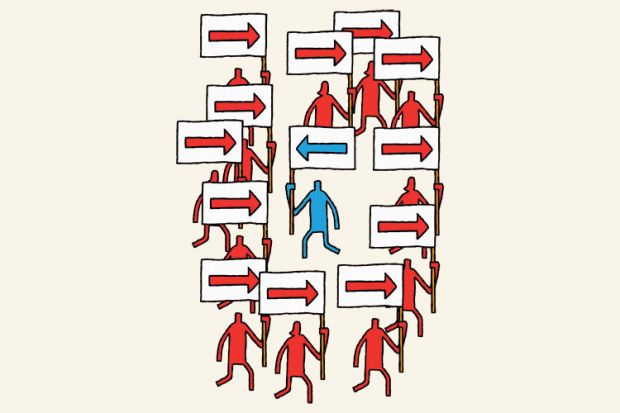

The language departments were keen to maintain a mandatory link between studying the language and the literature. The argument was that a university has to be more than just a language school. Whatever the merits of this line of reasoning, the reality was that it put many students off learning a language. Students complained that too much time was devoted to literature, when all they wanted to do was learn the language, and preferably, for many of them, in a business context.

Yet with the right mix of courses and content, literature and more practical applications can in fact be mutually reinforcing.

This issue is likely to remain contentious because of the widely diverging backgrounds of those who are teaching and researching languages at the tertiary level. However, there is now considerably more variation in what universities offer, and dedicated language for business courses and related options are more common, often within international business and MBA programmes.

In our globalised world, there are two parallel tendencies. On the one hand, the dominance of English arguably reduces the need for other languages. But on the other, it remains true that access to a foreign culture, its business environment and indeed most other aspects of life, remains largely closed without the requisite language skills.

Indeed, my own career changed fundamentally after studying German together with economics and business administration. Not only did this combination lead me to Germany, but it also created a completely new career path within academia. Even though I presently teach and work almost entirely in English, being able to speak German facilitates integration into university life and society. Furthermore, knowing German enables me to understand the problems that my own students have with academic and business English.

Even if one can get by in English, the benefits of learning other languages remain substantial. Such capabilities open up all sorts of doors: career-wise, culturally, intellectually and, not least, socially. After all, some of my best friends are avid readers of Goethe and Schiller; and on occasion, so am I.

Brian Bloch is a journalist, academic editor and lecturer in English for academic research at the University of Münster.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login