The good news for universities: the sector's surplus grew to record levels last year.

The bad news for university staff: part of the reason why was that pay packets did not.

Tight control over staff expenditure - universities' biggest outlay - and strong growth in income from overseas student fees were among the key factors in the sector's strong financial performance in 2010-11, as seen in figures compiled for Times Higher Education by accountancy firm Grant Thornton.

A collective surplus among higher education institutions of £1.2 billion, or 4.5 per cent of income (up from 3.1 per cent in 2009-10), appears sound. But will it be enough to ride out the biggest shake-up of the academy's funding in decades? And to meet students' expectations?

The long-running trend is for capital expenditure to amount to a hefty 10 per cent of university income, says Andrew McConnell, director of the British Universities Finance Directors' Group (BUFDG), and he "can't see that diminishing when we've got students coming in paying higher fees".

With the fee cap rising to £9,000 this autumn, many predict that students will demand a better living and working environment.

"The question you have to pose", he adds, "is whether this surplus is sufficient to deliver that level of capital expenditure."

Crucially, many of the funding streams that universities currently rely on are about to change course dramatically; so for some, the picture could soon look a lot less bountiful.

The UK sector's collective surplus of £1.2 billion was up 50 per cent on the previous year's figure, according to Grant Thornton.

Growth in income was modest, up 3.8 per cent from £26.4 billion to £.4 billion. Funding council grants fell 0.8 per cent as government cuts began to bite; research income growth was below inflation at 1.7 per cent; but income from UK and European Union student tuition fees grew by 5.9 per cent. Endowment and investment income rose 11 per cent, although it remained low in real terms at £239 million.

Income from overseas student fees was the fastest-growing revenue stream, rising by 17 per cent to £2.8 billion - about 10 per cent of total income.

A recent report by the Higher Education Funding Council for England on the sector's finances says that the 2010-11 operating surplus is "significantly better than any previous year on record" (data were first collected in 1994-95) and "indicates that the sector is preparing for the transition to the new funding arrangements".

Encouragingly, there are "no institutions that are presently close to risk of insolvency", says Hefce's report, which is based on universities' annual returns for 2010-11 and their financial forecasts for 2011-12.

According to Grant Thornton's figures (based on the accounts data for deficits and surpluses before exceptional items), there were only 10 institutions in deficit, down from 25 the previous year and 33 in 2008-09.

Among universities, the worst figures were recorded by the University of Cambridge (-£10 million), the University of Aberdeen (-£7.6 million) and the University of Salford (-£818,000).

A Cambridge spokesman says: "A planned deficit in 2010-11 was the outcome of a strategic decision by council to mitigate the impact of the reduction in government support and the challenging economic climate."

An Aberdeen spokeswoman says the university set up a £6.9 million early retirement and voluntary severance scheme that will deliver recurrent savings of £7.8 million.

And a Salford spokeswoman points out that the institution "made a historic cost surplus in 2010-11 of £345,000, which is the figure Hefce monitors".

So which universities are in the strongest financial position? Among the 10 institutions with the largest surpluses, eight are Russell Group members - perhaps leaving them best prepared for any capital investment needed to satisfy the more demanding students coming their way in the high fees age. The others in the top 10 are Manchester Metropolitan University and The Open University.

A common factor is that a number of these universities underwent major restructuring in 2009-10.

The University of Leeds nearly quadrupled its surplus to £44.8 million, while King's College London nearly trebled its figure to £.5 million.

Both had instituted drastic staff cuts the previous year.

Perhaps the more pertinent figure for judging financial health is surplus as a proportion of income. And here, new universities were the best performers among the UK's larger institutions. Manchester Metropolitan returned a surplus of £34.9 million, or 14 per cent of income. Birmingham City University's and Coventry University's figures were around the 10 per cent mark.

Using this measure, some institutions returned a surplus that offered little room for manoeuvre. The University of East Anglia, for example, had a surplus of £1.7 million, but that amounted to just 0.7 per cent of income. For institutions in this position, any decline in an income stream, such as fees from overseas students, could have a significant deleterious impact (see below).

Institutions that rely heavily on funding council grants, meanwhile, may be nervous about the radically different funding regime being introduced this autumn, which will phase out teaching grants and channel funding through students and their loans.

Outside Scotland (where Scottish students are not charged fees and there is a greater reliance on funding council grants), small specialist institutions and post-92 universities were most likely to receive a high proportion of income from state teaching grants. For example, 50.8 per cent of Bath Spa University's income came from Hefce grant, with the University of Plymouth and Edge Hill University receiving 50 per cent each.

The fact that the sector managed to increase its surplus despite only modest growth in income suggests that universities must have kept a tight grip on costs in 2010-11. Certainly, staff costs rose from £14.46 billion to £14.64 billion, a 1.2 per cent rise. That was below the rate of inflation, so it amounted to a real-term cut.

The number of universities with staff costs greater than 64 per cent of income (Hefce recommends that they are kept below this level) rose from three to four.

Scottish and London institutions tended to have the highest staff costs, with De Montfort University (64.9 per cent of income) being the only exception in the top 10.

One factor in reining in staff costs was the 0.4 per cent national pay settlement in 2010-11. But universities would point out that despite this tight pay settlement, they still had to bear the cost of annual incremental rises for employees.

Another factor was restructuring through voluntary and compulsory redundancies. In 2009-10, universities spent £157 million on restructuring, so staff numbers must have fallen in 2010-11.

Restructuring costs fell to £37.2 million in 2010-11, suggesting that universities eased off their redundancy programmes, having made swingeing cuts the previous year.

Hefce's financial health report says that the real-terms decrease in staff costs is the first such occurrence since 1998 - an "important development, as income is projected to fall in 2011-12".

It confirms that the reduction in staff costs was caused by "a decrease in the total number of employees and a real-terms reduction in the average pay costs of employees".

However, the BUFDG's McConnell is cautious about the future.

"I don't know how long we can sustain sector awards of 0.4 per cent when inflation is running at 4 per cent," he says. "You would expect at some point that pressure is going to build to a demand for a pay increase."

The higher education unions, smarting from three sub-inflation annual settlements in a row, have entered a 7 per cent pay claim for 2012-13 and will argue that staff deserve a share of the extra income generated by higher fees.

Meanwhile, on pensions, there could be plus points for some institutions.

Post-92 universities may be grateful to the government for cutting future employer costs in the public sector schemes to which their staff belong.

In the pre-92 sector, the universities won their battle with the University and College Union to cut benefits in the Universities Superannuation Scheme (although the USS does not appear on institutional balance sheets).

However, they are likely to face an increase in their contributions to plug the £3 billion deficit identified by the latest USS valuation.

Many observers believe that the new fees regime and added competition between institutions will accentuate the stratification of the sector.

Commentators have suggested that the universities that will benefit are the elite institutions - which under the new system will be allowed to recruit as many high-achieving students as they wish - at one end, and at the other, those charging lower fees - which will pick up extra students through the government's new "margin" system.

Between those extremes, the "squeezed middle" could miss out, recruiting fewer students and thereby losing funding.

The 2010-11 financial data may offer some hints about the pressures being felt by different types of university.

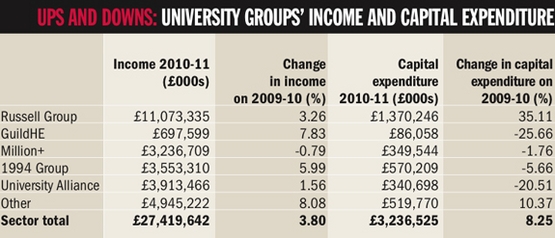

For example, the 20 Russell Group universities managed a hefty 35.1 per cent increase in capital spending, investing £1.4 billion in campuses and facilities, while the other mission and university groups implemented cuts.

There was a 25.7 per cent decrease in capital spending among GuildHE institutions; the University Alliance figure was down 20.5 per cent; in the 1994 Group, such spending declined by 5.7 per cent; and in Million+, the figure fell 1.8 per cent.

However, in the non-aligned universities, capital spending rose 10.4 per cent.

David Barnes, partner and head of education at Grant Thornton, says the strong commitment to capital spending in the Russell Group might reflect "confidence in its own position" or an acknowledgement of the fact that the group felt it needed to "do something to improve the quality of life for students" in preparation for higher fees.

Although the overall surplus reached £1.2 billion in 2010-11, did the sector store up enough in the good times?

When one takes into account recent low pay awards, cost savings through restructuring and the extra injection of funds from Labour's introduction of top-up fees in 2006, Barnes says that "you would expect there to be a year or two of big surpluses coming through. The question is whether you would expect a 4.5 per cent surplus, or 15 per cent."

But, either way, 4.5 per cent is "certainly a good surplus", he adds.

In future, borrowing costs could be a problem. Barnes points out that in recent years, universities have been able to borrow on "very preferential" terms - with low rates of interest and 25- to 30-year repayment periods due to the security of state funding and the stability of the sector - but this is likely to change.

"The issue for those universities is that [those taking out] any new loans for capital expenditure...won't be able to obtain those same loan rates," he explains.

And McConnell highlights Hefce figures that show that "debt servicing" - keeping up to date with debt-payment plans - ran at a level equivalent to 2.14 per cent of income in 2010-11. That is uncomfortably close to the overall surplus, he says. Universities would not want debt costs to eat into their surpluses, or worse still, swallow them.

With continued capital spending required to meet students' expectations, some universities, McConnell says, could face a perfect storm - "low surpluses with high capital expenditure requirements, diminishing student numbers and other sources of income".

Hefce concludes in its report that the sector is "financially well prepared for the new funding system". However, it predicts that surpluses will drop sharply in the 2011-12 financial year as teaching grants begin to decline.

And the funding council highlights "a large degree of uncertainty about how the new system will operate in the medium term ... in particular with regards to the policy of controlling student numbers. As the policy becomes clear we will need to reassess the future financial prospects of the sector."

The government has yet to confirm whether (and if so, to what extent) it will extend the number of contestable places under the AAB and core-and-margin systems beyond 2013.

Figures drawn from universities' accounts in 2010-11 give us some idea of how well they have prepared for autumn 2012 and beyond. It is now a matter of waiting: and if government reforms do create an increasingly stratified sector, different types of institution will face different types of test.

The big questions for university managers are, as yet, impossible to answer. How will institutions balance the risks of under-recruiting and over-recruiting students when the former could mean insufficient funding while the latter would mean huge fines? Which Russell Group universities stand to win or lose most from the competition for high-achieving students? How many students will choose their local further education colleges over their local universities? And how will the academy's "squeezed middle" cope with the loss of students to the bottom and top ends of the market?

Amid such uncertainty, an average surplus of 4.5 per cent offers scant protection - and it could easily be blown away by the harsh winds of change.

Regional disparities: but the elite look well set, wherever they may be

As you would expect, devolved education policy means that the financial picture for English universities and their counterparts in the rest of the UK looks very different.

In Scotland, where fees do not apply to Scottish students, universities remain more reliant on funding council grants. Three Scottish universities figure in the top 10 institutions most reliant on such grants, a list otherwise made up of small specialist colleges in England. The three are: the University of the West of Scotland (69.5 per cent of income), Glasgow Caledonian University (58.3 per cent) and the University of Abertay Dundee (55.8 per cent).

Of the 10 institutions in deficit, three are Scottish: the University of Aberdeen (£7.6 million), Queen Margaret University (£159,000) and the Glasgow School of Art (£26,000).

Queen Margaret had the highest borrowing levels of any UK university at 200 per cent of income - a figure the university says was related to the capital costs of the new campus it occupied in 2007.

A Queen Margaret spokeswoman says: "To facilitate this, significant borrowings were needed over a five-year period. These planned debts are now in the process of being repaid and will be significantly reduced by the end of the 2011-12 financial year. In the meantime, the efficient design of our new campus is already enabling us to make significant savings on day-to-day running costs."

The University of Edinburgh (£43.7 million) and the University of Glasgow (£10.4 million), both Russell Group members, recorded the biggest surpluses in Scotland.

And it is these institutions, along with the University of St Andrews, that are likely to reap the biggest rewards when Scottish universities raise the fees they charge to English students in 2012-13.

The University of Wales, which will cease to exist in its present form following validation scandals, did not return its accounts in time to be included in the survey.

The universities of Cardiff and Swansea returned surpluses of £9.4 million and £7.9 million, respectively.

In Northern Ireland, Queen's University Belfast, a member of the Russell Group, returned a surplus of £1.8 million - just 0.6 per cent of its income. It was outstripped by the University of Ulster, although it recorded another narrow surplus - £2.9 million, or 1.4 per cent of income.

Overseas bounty: but what happens if they can't come?

At face value, the growth in fee income from non-European Union students sounds like a success story. However, there is also cause for concern.

Some institutions have become "very dependent" on overseas student numbers, says David Barnes, partner and head of education at Grant Thornton UK.

This could be a problem because tougher visa rules are expected to bite in 2012. Some institutions are already seeing a "drop-off" in overseas student numbers as a consequence of border control restrictions, Barnes adds.

Overseas student income "makes a reasonably high contribution" to universities' overall financial health, he says.

So, with such income representing the only fast-growing revenue stream for some universities, any damage wrought by visa restrictions could severely affect institutional finances.

"If that falls away, it will have a direct impact on the surplus and cash coming in in the future," Barnes warns.

The Higher Education Funding Council for England's financial report notes that the extent of the reliance on overseas income varies, ranging from 0 to 35.8 per cent of institutions' total income.

"The 20 institutions recording the most income from overseas fees account for nearly 50 per cent of the sector's total," it says.

Lion's share holders? Unequal distribution of income across the sector

With four new members joining in August, the Russell Group is edging close to marshalling half of the sector's income.

Last month, it was announced that Durham University, University of Exeter, University of York and Queen Mary, University of London would leave the 1994 Group and join the elite body of large research-intensive universities.

In 2010-11, the 20 Russell Group members had a combined income of about £11 billion, accounting for 40.4 per cent of the UK sector's income from all sources.

But when the four new members and their combined 2010-11 income of about £1 billion are added in, the total is £12.1 billion - meaning that Russell Group members accounted for 44.3 per cent of the academy's income.

The Russell Group is already viewed as a powerful lobby that has the ear of government. With its new members and the added clout yielded by their research and fee income, its influence is sure to rise.

As research concentration is accentuated and its members effectively escape the student-recruitment cap thanks to the coalition's AAB and core-and-margin plans, the Russell Group may soon take the lion's share of the sector's income.

Figuring it out: the tables explained

The table (see related file, right) gives data for the financial year ended 31 July 2011. It includes all higher education institutions listed on the funding councils' websites. All decimal figures are rounded to the nearest whole number. The following institutions' accounts were not available at the time the data were compiled: University of Wales, Stranmillis University College and the University of Glamorgan.

Net surplus/deficit: this is the difference between income and expenditure. It does not take into account any profit or loss made on the disposal of assets. Deficits are shown in parentheses.

Funding council grants: all Higher Education Funding Council for England/Higher Education Funding Council for Wales/Scottish Funding Council grants as well as from other public funding bodies such as the Training and Development Agency for Schools.

Research grants and contracts: all research income from all sources except Hefce/HEFCW/SFC research grants.

Tuition fees and contracts: tuition fees from UK and European Union students, plus other teaching income relating to education contracts, short courses, etc.

Overseas fees: tuition fees received from full-time and part-time students outside the UK and EU. Where no figure is given, overseas fees were not differentiated in the accounts.

Other income: income from catering, residential and other activities. May also include income from subsidiary companies.

Total staff costs: total wages and salaries, including benefits, social security costs and pension contributions.

Interest paid: includes interest on pension liabilities. Institutions with zero borrowing may still have large interest payments.

n/a: not included in the survey last year.

* No figure published in accounts as the Guildhall School of Music and Drama is part of the City of London Corporation and is not a separate legal entity.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login