A few weeks ago, you might have heard that somebody took a steamroller to novelist Terry Pratchett’s hard drive. At the Great Dorset Steam Fair, an industrial beast named Lord Jericho was tasked with executing the last wish of the Discworld creator, who died in 2015 after a long struggle with Alzheimer’s disease: the utter obliteration of his unfinished works.

There are reasons you might not wish your last work to see the light of day. Sometimes, it is death, unpredictable and ineluctable, that wrenches a writer away from their work too soon. At other times, it is life itself that prevents us from polishing off what we seem to have been working on forever. But there can also be something alluring in the partial, the imperfect, the great unresolved. This is what comforts slowpoke academics like me when deferring their deadlines to another day.

In literature, Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s 1816 poem Kubla Khan is the archetypal unfinished work. Seemingly composed in a dream, Coleridge awoke from his reverie in the fullest throes of poetic inspiration, determined to record for posterity his exotic (if opium-invoked) vision of a Mongolian palace. Then the dreadful “person on business from Porlock” knocked on his cottage door, catastrophically interrupting him mid-flow. The vision vanished, leaving him only the dying embers of inspiration and 50-odd scattered lines.

Coleridge cursed those with a propensity to turn up at the door at an inopportune moment, but most of us see through the ruse. The person from Porlock is only a more sophisticated “dog-ate-my-homework” sort of excuse for not finishing something. We can all make embarrassed apologies or blame the modern equivalent of Coleridge’s interloper, the supermarket delivery person. But so many different things can genuinely obstruct and impede our progress.

There is, though, something infuriating in Coleridge’s insistence that a poem could come to him so fully formed, as though writing were only ever the obedient inscription of miraculous genius. This is a fantasy that, I suspect, not many of us have ever seen realised. Research and writing can be a painful slog, agonisingly eked out over weeks, months and years. But the Romantics were mischievous that way, happily dabbling in unfinished fragmentary forms, passing them off as creative exercises in the style of the ruins of antiquity.

In 1813, Francis Jeffrey, the severe editor of the Edinburgh Review, sardonically observed of such an offering by Byron that “The Taste for Fragments, we suspect, has become very general, and the greater part of polite readers would no more think of sitting down to a whole epic than to a whole Ox”. But while it would certainly be rude to send a modern journal editor an entire ox, allowing your argument to trail off mid-sentence is not an option for most of us.

In some ways, that is a pity. In their inchoate, visionary stage, our intellectual ambitions are brilliant and untarnished by our limited time and imperfect expressions. Unformed things never fail us, but real research often falls short of the expectations we had when we set out to delineate some scintillating new thought. This is what discourages me when I confront the blank screen.

Scholarship is an act of reconciliation. We make peace with the disappointment of not having quite accomplished what we intended. Sometimes, that irritable, perfectionist impulse makes us hold on to things for too long, as though we could not read enough 18th-century history or studies of the microbiology of ants to thoroughly satisfy our sense of scholarly context. If we’re lucky, some kindly editor or grumpy head of department will eventually wrench the research from our hands and point us in the next direction.

This is a necessity when you are locked into the fixed timeframes of national research assessment mechanisms, but it can be rather unpalatable not to be able to write to our own rhythms. That isn’t because we are precious about our work, or indolent in our productivity, as some suggest. It is because we know the culture sanctioned by this timetabled productivity curbs the freedoms and independence that can make scholarly work original, illuminating and important.

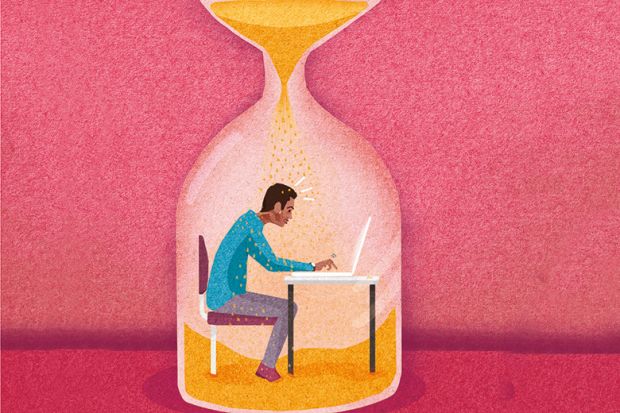

Indeed, the deadline is perhaps the thing an academic fears most. It is the schoolroom spectre that pursues us every day, howling in our ears, catching at our tails, threatening to drag us into despair. I admire you if you are the sort to dispense with a deadline smartly, boxing its ears and neatly kicking it into space. In these matters, I err towards Truman Capote. In 1968, he failed to meet his submission deadline for his posthumously published novel, Answered Prayers. “Posthumous” is how he described it while he was still alive. “Either I’m going to kill it,” he said laconically, “or it’s going to kill me.” He won a reprieve until 1973, but missed that deadline, too. And the one in 1976. And the one in 1981. The recorded cause of his death in 1984 was liver disease rather than literary composition, but, either way, the book still wasn’t finished.

Two years later, it was published anyway, the public’s appetite for fragments still apparently not quenched entirely. It’s a lively and salacious read. I’d tell you what happens, but there’s someone knocking at the door. Probably on some business from Porlock.

Shahidha Bari is lecturer in Romanticism at Queen Mary University of London.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Tyranny of the deadline

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login