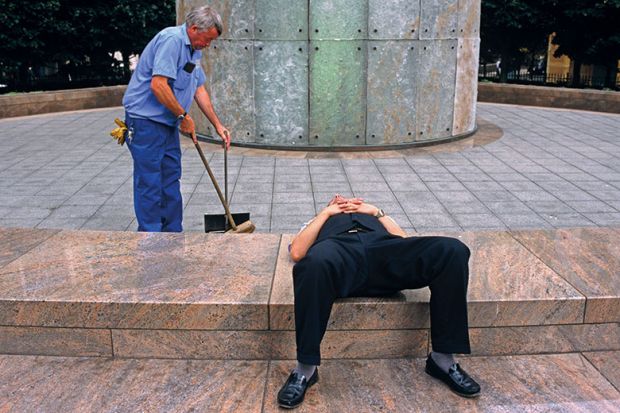

Academics are often asked to “do more with less” as they navigate increasingly complex, unpredictable and demanding working environments.

However, it is not simply heavy workloads that can cause university staff to crack under pressure. New research into the causes of academic stress indicates that “change fatigue” can prove particularly damaging to well-being in the workplace.

Change fatigue is defined broadly as a sense of passive resignation or apathy towards organisational changes. It occurs when people believe that too many changes have taken place too quickly – a phenomenon that many university staff may recognise.

Analysing responses from 4,500 academics, my collaborator Siobhan Wray, from York St John University, and I found that change fatigue appears to be endemic in higher education. Six out of 10 people agreed that too many changes had been introduced in their institution, while only 6 per cent disagreed with this statement. A considerable majority also said that they were tired of all the changes they had experienced, saying they were “overwhelming”. As one lecturer commented: “Things change rapidly without warning. Goalposts move in such a way that you no longer have a chance to score, and this leaves you reeling.”

Our research suggests that the way that change is managed and communicated is a significant source of stress for academics. Satisfaction with the management of change is substantially lower than national benchmarks for employee well-being set by the UK Health and Safety Executive, according to our research, which will be published later this year.

More than six out of 10 respondents indicated that they are “seldom” or “never” consulted about changes at work that directly affect them. One lecturer remarked that “changes are made with no consultation or discussion with academic staff” and that “many seem random and ill-thought-through”, adding that he was “no longer clear about my roles and responsibilities”. “Last year I was asked to redraft a programme handbook four times between June and August using different formats, with no rationale provided for this,” added another academic.

Some might wish to dismiss such complaints as the moans and groans from staff resistant to any sort of innovation or suggestion that things could be done better or more efficiently. In fact, combating change fatigue may be essential in order to retain your best staff and make sure that change initiatives are successfully implemented.

Our survey found that academics who reported more change fatigue were at greater risk of burnout, which is characterised by emotional exhaustion, cynical attitudes towards others and reduced feelings of personal accomplishment. Cynicism is a particularly toxic response to excessive change that can quickly transmit itself through an organisation and foster a general atmosphere of negativity. Employees who resist such initiatives may even try to actively sabotage them.

We also found that academics who were more fatigued by change typically worked longer hours, believed that their personal life suffered because of their work and felt less able to switch off from work worries and concerns.

Those who feel that they are experiencing unreasonable or unnecessary change without a period of consolidation typically believe that their contributions or their opinions do not matter, which may cause them to become alienated from their organisation or even their discipline. We found that academics who reported more change fatigue tended to be less satisfied with their general working conditions as well as the more intrinsic aspects of the job such as teaching and conducting research.

Those who experienced more change fatigue felt less capable of making decisions and found it difficult to sustain concentration. Over time, change fatigue is also likely to stifle the innovation that is essential in academic work and to discourage the organisational citizenship behaviours that underpin personal effectiveness. As one respondent said: “The demands of the job increase so rapidly that there is little time to train, or even to seek help to deal with new demands in a better way – so it all becomes a vicious circle.”

Our findings are worrying. The extent and impact of change fatigue have serious implications for the long-term health and effectiveness of academic staff and the sustainability of the sector. Respondents to our survey were almost unanimous in recommending that a period of stability is required in UK higher education.

The sector will inevitably continue to change to adapt to market conditions and to remain accessible, accountable and relevant.

Nonetheless, universities need to take change fatigue seriously and manage transitions and uncertainty more effectively, not only to increase their employees’ acceptance of change but to protect their well-being and effectiveness through the change process.

Gail Kinman is professor of occupational health psychology at the University of Bedfordshire.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login