The last time I spoke to my dad, he told me to “pack in all this university shit and get a real job”.

That was 18 months ago, and I had just met up with him for the first time in a long time to celebrate the fact that I had been offered a full scholarship for PhD study. It wasn’t the first time he’d said it, and he wasn’t the only person in my family to have expressed that sort of sentiment, but it was a blow all the same. We didn’t fall out because of that encounter necessarily; we just don’t speak any more. I suppose we’ve realised that we don’t really have anything to say to each other.

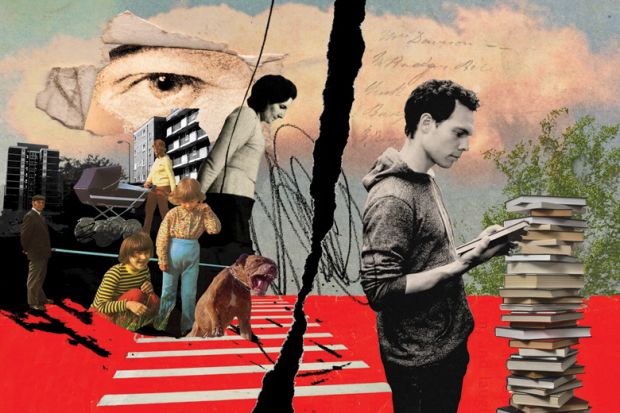

I grew up on a council estate in Salford, and I was painfully aware of just how little money my family had even compared with the other members of our aggressively working-class community. And I don’t use the word “aggressively” lightly: whenever I return home, I’m very aware of the fact that I’m returning to a sea of spiteful glances and waspish remarks that seem to be intended to counteract some imagined condescension on my part. Although there are definite exceptions – I still have friends and family who I know are proud of what I have accomplished – when taken as a whole the community’s message is clear: you have turned your back on your roots, so your roots don’t want you any more.

I imagine that some people reading this are already beginning to feel a bubbling sense of outrage at my suggesting that the working classes are peculiarly prone to a kind of malicious anti-intellectualism, and up until a few weeks ago I probably would have been right there with you. After all, this is my own heritage I am denigrating. But nor am I some kind of self-loathing proletarian: I’ll be the first to admit that I will never not be working class, no matter how many craft beers I drink or how many Danish police procedurals I watch.

However, the recent referendum on the UK’s membership of the European Union has asked us to choose one of two sides: in or out? Perhaps the most troubling dichotomy to have come out of this, for me personally, is the one that pits so-called university-educated experts (of whom Brexit campaigner Michael Gove said people were sick) against the “common man” (or woman).

The problem with this distinction isn’t just that it tricks people into internalising this oxymoronic notion that experts don’t know what they’re talking about. It is the insidious suggestion that there is a clear and explicit difference between those who are educated and those who are poor. This kind of rhetoric only exacerbates the kind of “get a real job”, anti-education mentality that is already all too common in deprived communities, and that holds back their own advancement.

I was very lucky to receive funding for both my master’s and my doctoral studies. I had no financial support to draw upon from home: without the generosity of my institution and a, frankly, traumatic amount of hard work at my end, any possibility of graduate study would have remained a pipe dream. I can’t imagine how much harder it would have been for me if the entire country had been complicit in the manufacturing of an intellectual civil war between academics and people of my background.

I am not sure what the long-term fallout of this kind of discourse will be, but I will hazard a guess. The make-up of the postgraduate student population in this country is already overwhelmingly middle- to upper-class – unsurprising, considering the fact that governmental financial support for master’s degrees is being made available only from the coming academic year (with loans for doctoral study not available until 2018‑19).

It is already difficult to integrate into such a community when your accent, clothes and formative experiences so clearly mark you out as different. If we in this country are going to foster an environment in which working-class children are told that education is “not for them”, we will reach a point where the distinction between “educated” and “poor” people becomes cast in stone. The label “working-class academic” will become a contradiction in terms.

I, for one, have no interest in becoming a walking oxymoron. Here’s hoping that even if the worst comes to the worst and these despicable ideas take hold of our working-class communities, there will still be a few kids out there willing to play against type.

Ryan Coogan is a PhD student studying English literature at Liverpool John Moores University.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: University isn’t for you: what ‘experts’ debate tells the working class

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login