The proportion of English undergraduates telling a major survey that their degree was poor value for money has exceeded the proportion who felt it was good value for the first time, with concerns focusing on low contact hours and delays in returning assignments.

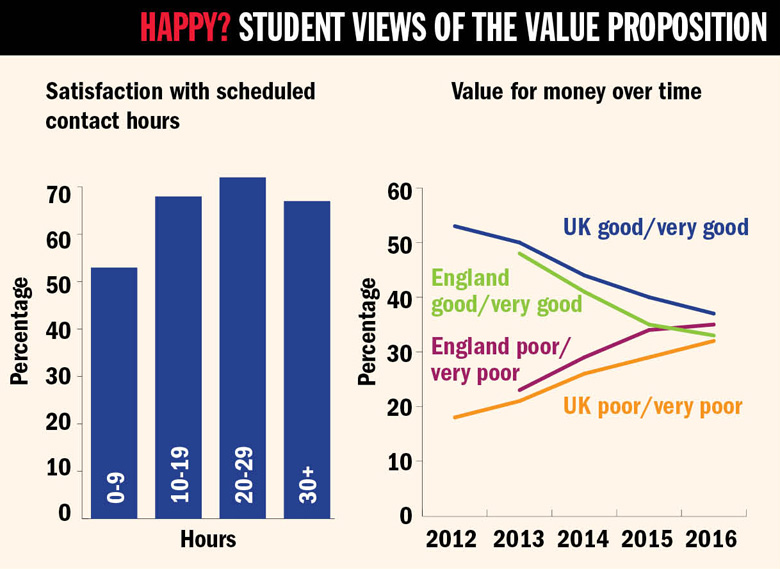

The annual student academic experience survey conducted by the Higher Education Policy Institute and the Higher Education Academy found that 35 per cent of English-domiciled respondents believed that their time at university had been poor or very poor value for money, with the 1 percentage point increase on last year continuing a trend that has been evident since the raising of the tuition fee cap to £9,000 in 2012.

Thirty-three per cent of English undergraduates said they felt that they had received good or very good value, down from 35 per cent in 2015.

This year’s survey is the first in which all student participants on three-year courses will have taken their courses under the £9,000 fee regime.

The findings emerge as ministers consider increasing the fee cap beyond £9,000, in line with inflation, for English institutions that perform well in the forthcoming teaching excellence framework.

But the survey, based on the responses of 15,221 undergraduates, found that students at universities across the UK felt that value for money was getting worse, even if they did not have to pay £9,000 fees.

The UK-wide proportion of students who felt that they received good value stood at 37 per cent this year, down three percentage points year-on-year and hovering five percentage points above the proportion who felt that they received poor value.

Students at specialist and Russell Group institutions were most likely to feel that they received good value (42 and 40 per cent, respectively), while those at post-92 universities were least likely to believe this (34 per cent).

The survey found that only 8 per cent of respondents supported the Westminster government’s plan to allow universities deemed to provide excellent teaching to raise their fees in line with inflation, with 86 per cent opposed. As their preferred way for institutions to save money, nearly half of all respondents named spending less on buildings and sport or social facilities, with one in five saying that giving academics less time for research or lower salaries would be a good option.

However, little more than one in five students (22 per cent) now believes that the government should pay the full cost of their higher education.

Sorana Vieru, the vice-president (higher education) of the National Union of Students, said that the government should stop “heaping more debt on to students”.

“The Hepi-HEA survey provides us with yet more evidence against the previous coalition government’s argument that raising tuition fees would result in improving the student experience, while sky-high tuition fees are fuelling a continued decline in student perceptions of their degree’s value,” Ms Vieru said. “The results show that there is absolutely no justification for raising tuition fees further, and doing so will be hugely damaging to students and to the future of higher education.”

Overall, 85 per cent of students questioned said that they were satisfied with their university experience, down from 87 per cent last year.

However, perceptions of value for money appeared to be dragged down by concerns about limited contact hours. The survey found that UK students had an average of 13 and a half contact hours each week, but that 29 per cent had nine or fewer.

Only 53 per cent of the students with nine or fewer hours of teaching were satisfied with their contact hours, compared with about 70 per cent of undergraduates with between 10 and 30 hours.

Despite this, four in 10 students admitted that they did not attend all their contact hours. One of the main reasons given for this was undergraduates’ ability to access notes online instead, particularly at Russell Group universities.

Nick Hillman, Hepi’s director, said he believed that perceptions of value for money were the result of concerns about contact hours, combined with the emergence of a consumer mindset among students and insufficient efforts by universities to explain how fees were spent.

“Despite what academics and policy wonks often say about contact hours, students really care about contact hours, regardless of whether they are wrong [to do so] or whether it is too simplistic to measure them,” Mr Hillman said.

“Universities need to explain why their contact hours are reasonable for particular courses – it may be that there is greater expectation of independent learning – but demand for additional contact hours is unlikely to disappear, so it may need to be tackled in other ways, too, including giving consideration to increasing contact hours.”

Workload and teaching issues

The survey confirms continuing and widespread variation in the total workload of students on different courses, with undergraduates on subjects allied to medicine spending an average of 47 hours a week working, including independent study and placements, compared with students enrolled on mass communications and documentation courses, who spend as little as 25 hours working.

Students had mixed views about the quality of teaching. Just over 60 per cent of students felt that most of their staff were supportive, while about 75 per cent felt that most staff worked hard to make subjects interesting and encouraged them to take responsibility for their own learning. Just under half felt that the majority of their teachers motivated them to do their best work or helped them explore their own areas of interest.

In a finding that could have implications for the TEF, Russell Group institutions tended to have the lowest scores for measures of teaching quality, with specialist and post-92 universities performing better.

In a new question this year, the survey also reveals a significant gap between many students’ expectations of how long it should take for their assignments to be marked and returned. While students’ expectations were met or exceeded in 54 per cent of cases, they were not in 46 per cent, and there were several disciplines – communications, business and education – where they were not met in the majority.

Forty-three per cent of students felt that it would be reasonable to receive their assignments back within a fortnight, but this happened in only 22 per cent of cases. A quarter of students said that it took up to four weeks to get their work back – a situation that only 12 per cent found acceptable.

Mr Hillman argued that it was again a case of managing expectations, cautioning that pushing academics to return all work within a week or two would likely lead to poorer quality marking. But he highlighted that feedback was the area of the National Student Survey where undergraduates tended to be most dissatisfied and that, “the quicker you get your work back, the more the written comments are helpful”.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: More English think degree is poor value for money

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login